How Our Understanding of Academic Rigor Impacts Online Learning

Published by: WCET | 6/2/2022

Tags: Online Learning, Research, Standards, Student Success

Published by: WCET | 6/2/2022

Tags: Online Learning, Research, Standards, Student Success

We live in a drastically different world than we did just a few years ago. In particular, the higher education part of the world has seen some challenges – and has changed in response. Today’s higher education environment has shifted, as you well know, to either partially or fully online.

But we have not lost the need for for quality learning, no matter the modality.

Today we’re excited to welcome Amy Smith to discuss rigor in online courses and what elements of quality teaching and learning programs ensure a rigorous course. Thank you Amy for this excellent discussion!

Enjoy the read,

Lindsey Downs, WCET

Higher education is being disrupted more than ever.

How we deliver education has been forever changed by the pandemic-driven rush to online learning. Prior to March 2020, only about half of students took at least one class online, but then online learning became a necessity for all, practically overnight. Now, learners have new expectations and desires around how higher education is delivered and accessed, with six in ten people saying they prefer fully online or hybrid education, even if the pandemic was not a factor.

However, there is also a risk amid this innovation that the quality of higher education could be diluted if we don’t establish standards to ensure that the delivery of virtual learning—both by traditional institutions and new providers—can meet learners’ needs. So, how do we begin to define what makes a course rigorous?

Academic rigor is widely considered to be an essential component of the quality of higher education, but research shows that faculty and students define rigor quite differently:

Non-traditional students, who are often taking classes online, balancing life and education, and entering college with diverse backgrounds, may have a different understanding of rigor altogether (Schnee, 2008; Campbell 2018).

The key for higher education is to marry these various perspectives and focus on what elements are most critical for setting up students for long-term success. In that way, we can begin to define what makes an online course rigorous for the modern learner.

In my years as an associate provost and dean and now in my role of leading the research arm of StraighterLine, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about academic rigor and how it is defined by various stakeholders. As a faculty member, I felt I knew what rigor was when I saw it. As a student, I knew what rigor was when I experienced it. So why talk about rigor? Because talking about rigor keeps us grounded in quality—the one thing every provider of education should offer their students.

To help bridge the gap between the faculty and student perspectives, I reviewed the existing research and formulated a definition of academic rigor that can serve as a baseline for discussions in higher education.

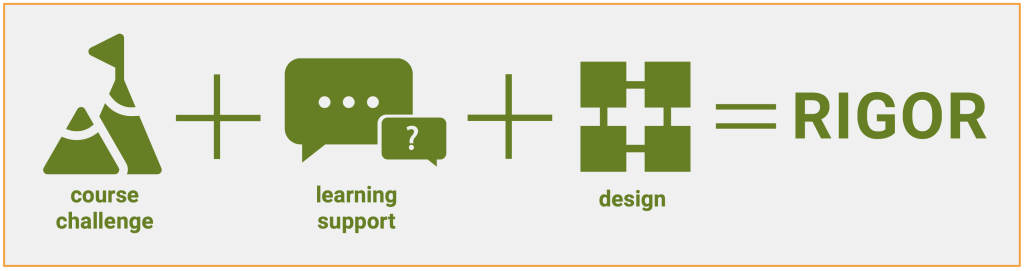

For today’s learners, it’s clear that rigor is reflected in a combination of course challenge, learning support, and design. The variables within each area can be turned up or down, but each must be present, and they need to move in relation to one another. This means providing high levels of support and good course design for a course that is particularly challenging or reducing the workload of a course if its design is lower quality and forces learners to invest more time to understand the material.

An online course environment adds a layer of complexity for students and demands more thoughtful learning design to arrive at an appropriate level of rigor: the distinction between being rigorous versus merely difficult becomes even more important. Students can often be “challenged” by unclear expectations and a burdensome workload without experiencing all the aspects of a truly rigorous learning experience. In fact, research has found that non-traditional and online students generally perceive a higher level of challenge in postsecondary courses than do their in-person counterparts (Barrett, 2015).

This makes the design of online courses particularly critical. “Course clarity and organization” are prerequisites for an appropriately rigorous online course (Duncan et al., 2013).

Learning support, which is critical in all courses, also needs to be more intentionally designed in online programs. There are far fewer opportunities for casual observation of a students’ work and whether they are struggling with a concept. Therefore, regular check-ins, low-stakes assessments, and easy access or quick referral to tutoring, academic counseling, and other support systems need to be built into online courses.

In the issue brief Rigor and College Credit, I make the research-based case for why online courses must maintain a balance among course challenge, learning support, and design. It’s ideal to put the research into practice. For example, courses at StraighterLine are intentionally designed to maintain the balance among these three elements, while paying particular attention to the student experience. This brief is intended to provide a framework for a larger discussion:

As higher education explores ways to provide more flexible, responsive pathways to learners, we must increasingly move away from time-based measures of learning. To do so, we will need a more informed way of understanding academic rigor and its connection to outcomes. It’s clear that course challenge must be married with both design and learning support — but within that, there’s ample room for experimentation and discussion.

Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs and Provost, Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design

Barrett, B. (2013). Creating Structure Out of Chaos in a Virtual Learning Environment to Meet the Needs of Today’s Adult Learner

Campbell, C. M. (2018). Future Directions for Rigor in the Changing Higher Education Landscape

Draeger, J., Hill, P. P., Hunter, L. R., & Mahler, R. (2013). The Anatomy of Academic Rigor: The Story of One Institutional Journey

Draeger, J., Hill, P. P., & Mahler, R. (2015). Developing a Student Conception of Academic Rigor

Duncan, H. E., Range, B., & Hvidston, D. (2013). Exploring Student Perceptions of Rigor Online: Toward a Definition of Rigorous Learning

Graham, C. & Essex, C. (2001). Defining and Ensuring Academic Rigor in Online and On-CampusCourses: Instructor Perspectives

Schnee, E. (2008). “In the real world no one drops their standards for you”: Academic Rigor in A College Worker Education Program

Wyse, S. A. & Soneral, P. A. G. (2018). “Is This Class Hard?” Defining and Analyzing Academic Rigor from a Learner’s Perspective