The Great LMS Review Adventure

Published by: WCET | 2/4/2016

Tags: LMS, Managing Digital Learning, Practice, Technology

Published by: WCET | 2/4/2016

Tags: LMS, Managing Digital Learning, Practice, Technology

Who wants the best LMS? We all do! How do you pick the best LMS?

*cricket chirp, cricket chirp*

A choice of a Learning Management System (LMS) is a critical one for colleges and universities on so many levels – it is the most important academic technology system in the majority of higher education technical infrastructures and has tentacles into every facet of learning and teaching. This brief post will share some lessons learned from a 14-month long LMS review process at Cuyahoga Community College.

Picture this – a large community college with approximately 23% of FTE attributed to online courses, and another 8% attributed to blended or hybrid courses. With an annual student population of 52,000, this Midwestern college has a strong shared governance structure with a well-established faculty union. Now picture this – the college has used Blackboard since 1997. It’s a “Wild Wild West” model of online courses, whereby faculty can put any course online and there are no systemic processes for instructional design, accessibility, or quality assurance in those courses.

This was the case as Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C) set off on its adventure of analyzing and selecting the best LMS for Tri-C.

And that’s an important distinction. From the very beginning, the premise of the review was not to find and select the best LMS available. It was to select the best LMS for the college. Why does this matter? Culture. Culture is so critical in the adoption of online learning, the acceptance of its legitimacy and value, and the time and effort put into creating courses and supporting them. In this strong shared governance culture, it was important that from the very beginning, we weren’t looking for the best system, we were looking for the best fit. The process that found us that best cultural fit could be broken into 6 primary phases:

1) Initiation

So why do you want to review your LMS? Is your contract up and you’re not feeling the love? Maybe your LMS is being phased out, or you’re unhappy with recent functionality changes. In the case of Tri-C, we were coming out of a major Title III grant, which funded Blackboard systems. We also had been a Blackboard school for about 18 years and had a list of frustrations about functionality – specifically system “clunkiness” – that begged to be examined. And so we did. Tri-C has several committees that support technology within academics, and this project was initially supported by the Technology Forum Governance Council, a combined committee comprised of members of AAUP (American Association of University Professors) and Tri-C administrators.

From there, we approached the leadership of our Faculty Senate and the AAUP as well as the campus presidents and other critical stakeholders for an initial round of exploratory demos on February 14th of 2013. We were feeling the love from vendors, getting a lot of insights into the roadmaps of different LMSs, and even a couple add-ons. Faculty Senate leadership recommended full-time faculty to participate in the year-long LMS Review Taskforce, and every constituent group from administration was included: IT, procurement, legal, access office, student affairs, and academic executive-level leadership. We secured a project champion in one of our campus presidents, put together a project charter and got to work. A full list of taskforce membership can be found on the blog documenting the process, which also included a published list of attendance at Taskforce meetings – transparency was a key component of the process.

Because of the length and intensity of the Taskforce commitment, descriptions of what the work involved were created and disseminated at the very beginning for both faculty and administration and staff. The expectations were clear, and the Taskforce members committed to the length of the project.

The structure of the project management itself reinforced accountability and commitment. Small work groups were created of four to five people who could more easily arrange times to get together in between the Taskforce meetings, which occurred every two weeks. Activities were assigned and conducted in two-week “Sprints,” which enabled us to have a series of small, intensive work timeframes and avoid “initiative fatigue” so common in large institutions. Each work group had a lead who was responsible for the completion of those activities. The work group leads determined many of the activities and contributed to the agile nature of the project. The project plan was flexible, and continually adapted. This was truly a case of distributed ownership. The plan adjusted as new ideas were brought forward and new problems were tackled.

2) Input Gathering

Right from the bat we started gathering input. In a strong shared governance environment, it was critical that not only were faculty voices heard, they drove the conversation, testing and selection. Our front lines with our students are faculty, and their belief in the best system for Tri-C students would be the critical piece of the decision-making process.

In order to get this party started, we brought in Michael Feldstein and Phil Hill from Mindwires Consulting to conduct a couple of full-day workshops to educate the LMS Review Taskforce so that we would start with a common core knowledge-base around the current marketplace as well as industry trends. Additionally, Mindwires conducted college-wide surveys of faculty, staff, students and administration as well as focus groups on each campus with the same constituent groups. It was valuable to use outside experts to come in and support this education process for the LMS Review Taskforce. It enabled our department – the Office of eLearning and Innovation – to remain the logistical and project management lead rather than getting into the weeds of gathering input. Additionally, using an impartial outside group ensured that there wouldn’t be any question of influencing that input. Because that feedback was a snapshot in time, we also created a continuous feedback form that students, faculty and staff could use at any time in the process to communicate with the Taskforce.

3) Needs Analysis and Demos

Immediately, the group jumped into the messy process of listing out the functional requirements in a Needs Analysis. You can find the messy working version here. Relatively simultaneous with this, a series of intensive demos were held with each of the five systems that were in the running: Blackboard, Brightspace by D2L, Canvas, MoodleRooms and Remote Learner (which is also a Moodle hosting service.) Though it might seem counter-intuitive to conduct those two activities relatively simultaneously, the timing strengthened the needs analysis process, as some of the LMSs that were being demoed had functionality that faculty at Tri-C were unfamiliar with, and decided that they wanted.

We did a comparison analysis of systems, almost an informal RFI process. The needs analysis, combined with the analysis of systems, enabled us to synthesize categories of needs and functional requirements to create the RFP.

4) RFP

The Request for Proposals (RFP) process was conducted by (you guessed it) the RFP Work Group. In addition to asking for information about the functional requirements defined from the Needs Analysis, questions were added that were future-forward in order to plan for what tools would help make students successful in 3, 4, or 5 years. We asked about ePorfolio functionality and digital badging capabilities, Competency-Based Education support, gamification potential and integrating in external tools as well as social media. The resulting RFP was pretty robust. It was also exhausting to read the results – so be prepared for reading hundreds of pages per vendor.

After the demos and the results of the RFP, a downselect was conducted which eliminated the Moodle-based LMSs. This downselect was conducted using a defined consensus decision-making process, which I’ll touch on later in the final step.

5) Testing

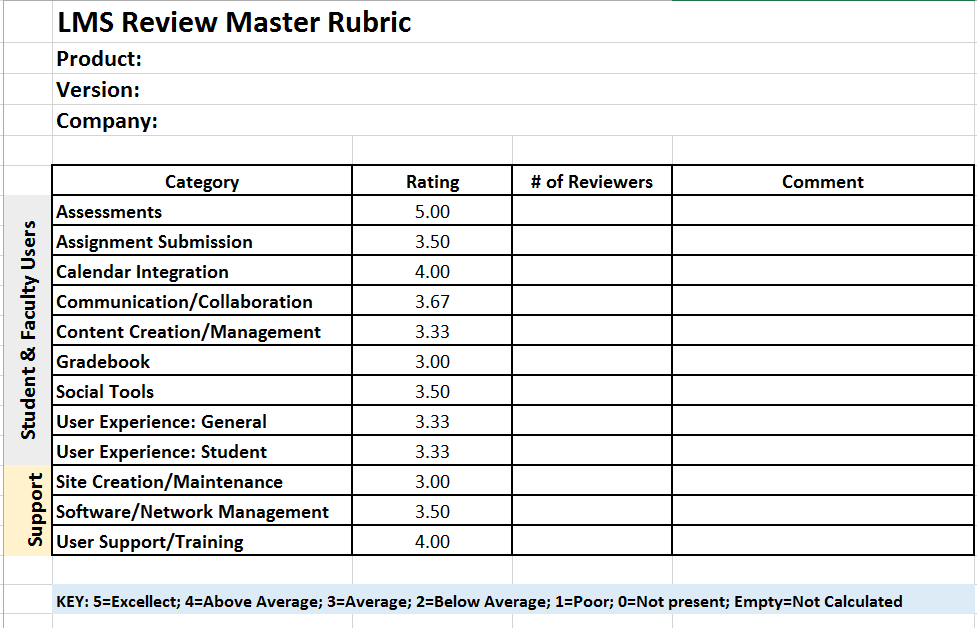

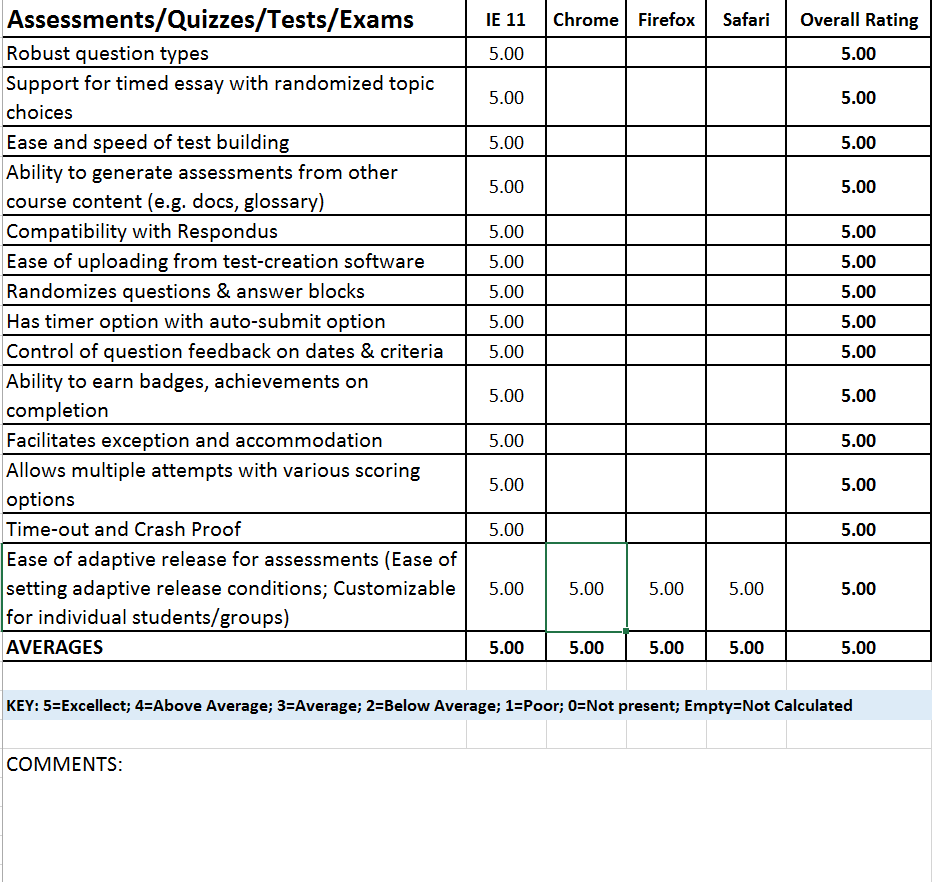

And then came testing! A series of sandbox environments were set up in each of the systems – one that was a “blank” course, one that was an import of a course that had a variety of content, and one that was vendor-created. A rubric was created for testing that was aligned with the RFP (and therefore with the needs analysis.) The rubric then became a part of the final scorecard that was applied to the remaining systems.

The Student Experience Work Group and Mobile Learning Work Group combined forces to get feedback from students on the remaining systems. The testing process was one that – upon reflection – I would recommend changes to. Because the naming conventions in each of the systems are so different, a lot of valuable testing time was spent trying to figure out which functionality was parallel to what faculty had been used to in Blackboard. This could have been resolved by either changing the naming of tools in the other systems to match what faculty were used to, or by providing training in each of the testing systems. We did conduct multiple sandboxing sessions on each campus where faculty could stop in and explore the systems together. Faculty individually filled out their rubrics, which were then fed into the master rubric. Those results were then fed into the scorecard.

6) Consensus Decision Making

It was important from the very beginning of the process – and at the recommendation of Mindwires – that this not be an exclusively quantitative process. Each institution has a unique culture, and the LMS needs to fit and function within that culture. The conversation and discussion around the systems needed to be paramount, and this was reflected in the prioritization of the scorecard.

In order to accomplish a truly collaborative process, one without voting that might have traditional winners and losers, we utilized a consensus decision-making tool. First, the decision is clarified – what solution is being proposed, and what exactly does it entail. Then each individual involved needs to decide their level of agreement with the solution. There is discussion, and then everyone determines their level of agreement with the solution. It ranges from an enthusiastic “1” to a “over my cold dead body” at 6. The goal is to get everyone to a “4” – which basically says that though that individual doesn’t agree with the decision and wants that to be noted for the record, he or she won’t actively work against the decision.

On this one, everyone weighed in on the selection of Blackboard as a “1” through “3.” Success.

The most important part of this project, though, was the continuous, unrelenting transparent communication. This cannot be overemphasized, particularly in an environment of strong shared leadership and governance with faculty. Transparency is critical for everyone to know that there’s no agenda going on behind the curtain. To do this, we put together a Faculty Communication Work Group. There were faculty leads on each campus who were the “go to” people for questions. They led (and led well,) in partnership with Tri-C’s Interactive Communications department, an assertive communication campaign consisting of emails, videos, Adobe Presenters, posters, articles in the Tri-C newsletter, announcements on our intranet, and (as a throwback option) even paper flyers distributed in inboxes. The eLearning and Innovation team published regular blog post updates that flowed to a Twitter feed that was embedded within our college portal and the Blackboard module page. We kept a Communications Traffic Report in order to document the outreach, just in case someone managed to avoid every communication stream.

With the length of time of investment the college had already made in Blackboard, as well as the faculty time invested already in training and course design and development in the current system, Blackboard was the best choice LMS for Tri-C.

Subsequent to this process, we found out that we likely would never have access to Blackboard Ultra as a self-hosted institution. We explored moving to managed hosting, with the end goal of moving to SaaS and gaining access to Blackboard Ultra, but with the number and length of delays in its development, we decided instead to re-evaluate the system status for sustainability and to see if it still meets the needs of Tri-C in another year and a half.

Yes, that’s what I said. Revisiting in a year and a half.

The process ended up being an incredibly valuable one despite these late complications. It revealed a need for redesigned, college-wide faculty training and started the discussion of having shell courses for high-enrollment courses to provide accessible learning objects as resources for faculty.

Though it was exhausting and a nearly obsessive project that took incredible amounts of human resources, it built a robust discussion around online learning and how academics and student needs should drive technology discussions, not the other way around.

Find all the information on the process on our blog here, and search “LMS Review” to get all the historical blog posts.

Sasha

Sasha Thackaberry is the District Director for the Office of eLearning and Innovation at Cuyahoga Community College. In February she joins the team at Southern New Hampshire University as the Assistant Vice President for Academic Technology and Course Development. She can be found hanging out on Twitter @sashatberr or at edusasha.com.

2 replies on “The Great LMS Review Adventure”

Reblogged this on Sasha Thackaberry and commented:

Thrilled to have had the opportunity to guest blog for WCET! Check it out!

Thank you! A very informative look into the process of selecting/reviewing an LMS.