Evolving Evaluation: The Future of Faculty Development in the Digital Age

Published by: WCET | 5/19/2022

Tags: Assessment, Data And Analytics, Faculty, Online Learning, Privacy, Technology

Published by: WCET | 5/19/2022

Tags: Assessment, Data And Analytics, Faculty, Online Learning, Privacy, Technology

Don’t you just love performance evaluations? I do!

Just kidding, is there anyone who truly loves being evaluated on their job or teaching performance?

I do, however, appreciate the opportunity to learn and improve my work or teaching (etc.). So, perhaps I can say I appreciate when an evaluation provides me with such an opportunity?

Today’s post from Jenny Reichart, Faculty Development Specialist with the University of North Dakota, echoes this appreciation. Jenny discusses the rhetorical feedback triangle and its relevance considering faculty evaluations and development. I so appreciate Jenny’s exploration of the impact of learning analytics on faculty evaluations.

Enjoy the read,

Lindsey Downs, WCET

I remember my very first teaching evaluation in graduate school. I taught a lesson of my choice from The World is a Text (remember that one!?). As an emerging queer theorist and televisual studies scholar, I chose Katherine Gantz’s text “Not That There’s Anything Wrong With That” analyzing the Seinfeld episode “The Outing” (I’m really dating myself here, aren’t I?). I presented my polished lesson to a group of my peers, many of whom I’d been friends with for years. I received some JIT formative feedback from them and our enthusiastic instructor in this mentored teaching program for English master’s students. I benefited from what many novice college teachers do not get to experience: a low-stakes evaluation in a simulated teaching environment with people I knew and was comfortable with. This is about as emotionally safe as one can get for formative feedback.

And–I still remember that feedback–from the instructor: “Try using more guided questions than general questions to elicit student responses; from a peer: “Don’t state that your subject matter isn’t as extreme as something and then name that extreme something because you’ll derail your students with the more extreme topic.” Good advice for any nascent teacher.

I distinctly remember specific details about that feedback from that one half hour even though it took place over 13 years ago. I remember the feedback, the text, the author, myself, my peers, and my instructor. What I don’t remember in that lesson and that room was a computer (which seems so bizarre now).

Fast forward to my first long-term teaching appointment where there were computers in the classrooms and “real” students. I remember many of the comments on my teaching evaluations from students: “Ms. Reichart was the only one teacher to check in on us after a campus evacuation” and “She was nice, but she had her favorites.” I had plenty of students say things about how I had helped them to improve their writing and critical thinking skills, but I don’t remember those comments as being truly formative for me. The comments that signaled that I had inadvertently made a student feel excluded or overlooked were the ones that kept me awake at night and haunt me still. Those are the comments that I took to heart and the ones that made me strive to become a better teacher and a champion for inclusion and belonging, because without those, learning doesn’t stand much of a fighting chance.

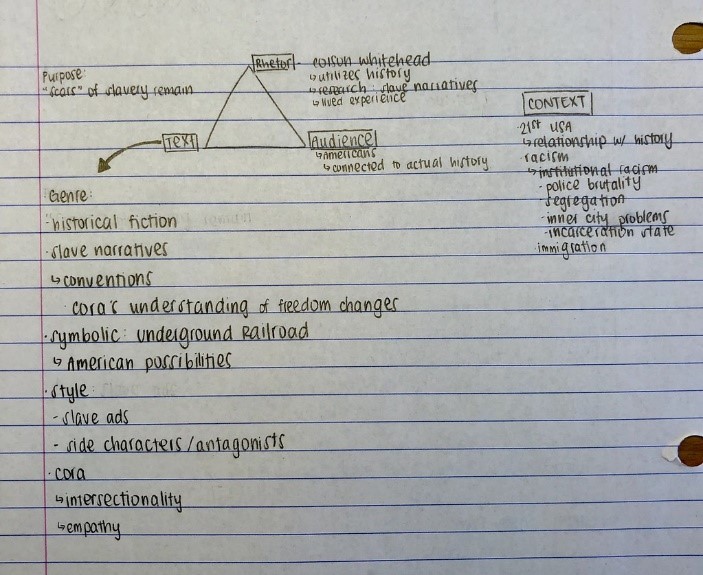

As a developmental English teacher, I frequently deployed the use of the rhetorical triangle in teaching students how comments or feedback are also up for analysis. When students read a work using this method, they can come up with something that looks like the following notes:

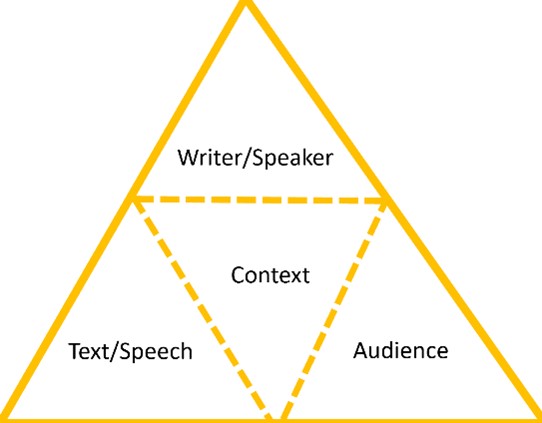

When students gave me an essay, that essay was the text, they were the writer, and as the evaluator, I was the surrogate representative of their audience. This all took place within the context of an English class in higher education. While the context stays constant like a spoke, the rest of the triangle turns like a laboring wheel. As I left feedback for my students on their essays, my comments became the text, myself the writer, and the students my audience. Especially in an online environment, this wheel turns and turns as our students respond back to us with questions and comments of their own. This is basic feedback cycle of the rhetorical triangle.

In the cases of direct feedback, such as when an instructor comments on student papers, an evaluator comments on teaching observations, and students evaluate for a teacher’s effectiveness, the model of the rhetorical triangle gives us an accessible framework (i.e., a simplification of reality). The model makes sense to most of us. It works for formative and summative feedback and formal and informal evaluations. Likewise, there has been much research into the area of high stakes assessment and its comparative value to low stakes assessments, or alterative assessments, in higher education; this has resulted from the proliferation of technology tools for formative assessment which have then in turn resulted in the proliferation methods and models for evaluating education technology. However, this critical focus is most often directed toward the effects on students and their learning, not faculty and their teaching. There has been some research that supports the benefit for faculty as well, such as this Harvard study on the benefits of low-stakes teacher evaluation in the form of peer evaluations. Similarly, the small group instructional diagnosis (SGID) method of having a trained third party solicit feedback from a faculty member’s student and report back works on this same premise with just another rotation of the feedback wheel to protect student anonymity and decrease anxiety to produce more formative feedback for the instructor. These types of evaluation have obvious benefits to the faculty member.

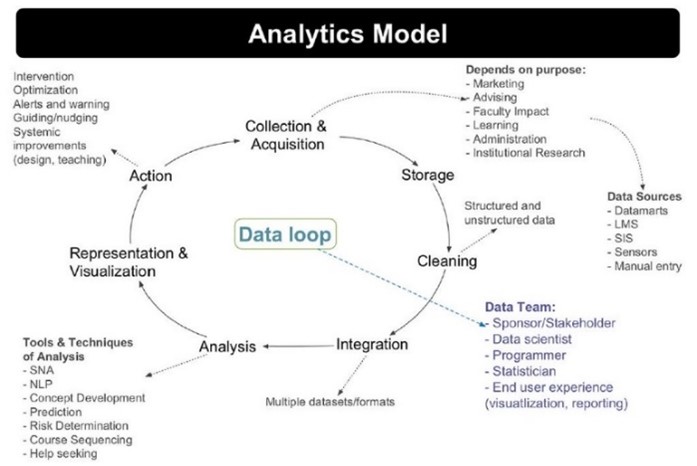

But in the Age of Big Data, the feedback loop is being replaced by the much more cumbersome model of the data loop. The joke of data paralysis as opposed to data analysis is a stark reality and a recognized barrier, and faculty who have been teaching outside of an LMS for most of their lives often struggle with the concept of learning analytics, and with good reason. They can feel even more lost, confused, and helpless when learning analytics are deployed to evaluate their teaching without clear communication on how the data is being collected, analyzed, and disseminated across leadership units.

Further compounding the issue is that many clinical courses employ lead instructors with a team of teachers working in the same course section in the LMS, and many colleges and universities hire faculty or subject matter experts to develop a course while other faculty members teach it. Most often, the course designer is responsible for the course content and organization and the course facilitator is responsible for the course instruction and grading. These are very different teaching tasks, and yet, students almost exclusively fill out end-of-semester surveys with the course facilitator in mind whether they were responsible for course content and/or organization or not.

Utilization of the rhetorical triangle framework falls apart with learning analytics. This is predominantly because we are now analyzing the context along with multiple contributing factors. Each assignment submission, time spent on a quiz, webpage visited and more are constantly tracked in the system. It is difficult to even articulate a direct correlation as you would in a physical classroom. There is a wealth of past research that correlates regular attendance with higher grades and learning outcomes, but even if we track a student’s time spent in a course, it is difficult to tell if students are actively learning or watching TikTok on their phones.

Simple rhetorical analysis requires us to ask these questions: who is the author, who is the audience, and what is the message? Running one simple report on student time spent in course does not necessarily answer these questions. We need to be highly intentional with this new wave of faculty evaluation, which is what learning analytics will undoubtedly become. Time spent in a course applies to instructors as well as students, and when administrators have access to these learning analytics and can compare one faculty member with another in the same program, we enter a new world of quantitative assessment that stands in stark contrast to the qualitative assessment of solo teacher observations of the past.

Faculty motivation, compassion, and engagement can be scrutinized in entirely new ways via learning analytics, so we need to be proactive in thinking about how to leverage these reports to improve faculty teaching, course development, and student outcomes. While the implementation of learning analytics in higher education has clear benefits for students, instructors, administrators, and researchers, there are immediate concerns about the effect “Big Data” has on student privacy, autonomy, and informed consent and long-term concerns about faculty simulating data to boost their overall analytics scorecard, especially where performance-based funding or priority course assignments might be factors. History has taught us what teachers desperate to help their schools and students can resort to concerning PBF as seen in the Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal. While the weaponization of learning analytics in faculty evaluation is a bleak prospect, we need to pave the way now for how we can use this evolving form of evaluation so that it becomes a sustainable practice for improving teaching and learning rather than an emergent mechanism for further blaming teachers in an increasingly data-driven world.

Higher Education Consultant, Speaker, and Author

1 reply on “Evolving Evaluation: The Future of Faculty Development in the Digital Age”

Thank you for your insights.