Defining Distance Education in Policy: Announcement and Call to Action

Published by: WCET | 3/7/2023

Tags: Distance Education, Managing Digital Learning, Regulation, SAN, State Authorization

Published by: WCET | 3/7/2023

Tags: Distance Education, Managing Digital Learning, Regulation, SAN, State Authorization

As previewed in a fall WCET Frontiers post, WCET and SAN have been conducting an analysis of “distance education” definitions used by federal agencies, states, accreditors, and others. The purpose of this review is to highlight the challenges and risks associated with navigating multiple sources of “distance education” definitions in policy. We are happy to share the publication of Defining “Distance Education” in Policy: Differences Among Federal, State, and Accreditation Agencies. Today’s post will review the report and share our key observations regarding this topic.

Navigating numerous, different definitions and applications of those definitions presents complications when it comes to developing institutional policies, procedures, standards, or guidelines. Reconciling these challenges is important as noncompliance could put institutions at risk of a variety of consequences including loss of access to student financial aid, repayment of student aid, accreditor sanctions, and others.

As we mentioned, the report is available on the WCET website today. Included in this report is a sampling of policies, and while it is not an exhaustive list, the review does highlight some of the more significant variations from federal, state, institutional accreditation agencies, professional accrediting agencies, and other national sources. We are also excited to discuss some of the key insights from the report with WCET members at this month’s Closer Conversation.

Definitions are used for a variety of purposes and multiple definitions of distance education may exist within the same organization or institution.

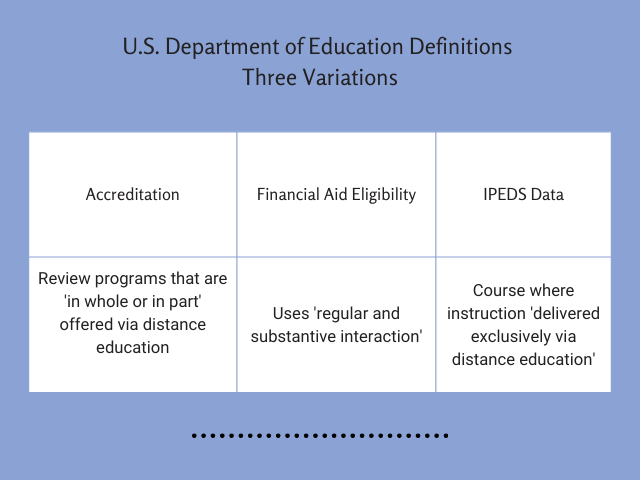

Many readers will be familiar with the definition of distance education used for Title IV financial aid purposes by the United States Department of Education (ED) at 34 CFR 600.2 and the statute on which ED regulations are founded, the Higher Education Act (HEA). However, those are not the only definitions of distance education that exist within their purview. ED-related definitions provide three different reference points and contain their own unique elements for institutions, organizations, and policymakers to understand, reconcile, and manage.

Not only are there three different definitions, but the variations in expectations are wide-reaching. At one extreme is a minimal “in whole or in part” as a distance threshold. At the other extreme is to count only those courses “delivered exclusively via distance education” with a few exceptions. As a result, the same course or program could be classified differently depending on which ED definition is applied at that moment.

Some organizations provide multiple sub-definitions related to distance education. For example, the Council on Social Work Education provides definitions of distance education generally, but also online, broadcast site, and correspondence. Furthermore, some organizations provide definitions not only of distance education, but of distance education courses and of distance education programs. For example, the National Association of School Psychologists defines both distance-delivered courses and distance-delivered programs with different thresholds of percentages that would constitute a distance-delivered course (at least 75% of the instruction) or a distance-delivered program (50% or more of the required courses). Further, the Higher Learning Commission defines distance education courses (75% instruction uses distance education technologies) and distance education programs (offered “in whole or in part” through distance education) with different thresholds as well.

Additionally, there are cases where the same agency applies the concept of distance education in greatly different ways depending on the purpose of each specific compliance or data requirement. Going back to the three ED definitions in play, where each definition is used for different purposes:

As you can see, the thresholds range from a minimal one for accreditation to a steep one for IPEDS data reporting. In between is the financial aid “regular and substantive” measure, which requires meeting multiple criteria.

Essentially, it means that when reviewing definitions, institutions must carefully note the purpose and application of the definition, and not assume that one organizational definition will apply in all scenarios.

Definitions in policy may not align with definitions in practice and institutions may choose strategies that best balance the spirit of compliance, institutional efficiency, and transparency.

A common theme we saw in definitions was around the physical separation of students and instructors, but the challenges lie in the variations that follow. For example, the threshold or specificity of the percentage of coursework or instruction that would constitute distance education varied significantly from organization to organization (and sometimes from within the same organization).

The reasons for these policy variations may not always be clear and this presents challenges to how different institutional stakeholders (i.e. institutional staff, faculty, students) may understand distance education. Some institutions utilize multiple definitions due to either various compliance or reporting requirements or based on the audience to whom it is communicated. For example, a more technical definition may be used for faculty or instructional designers, whereas a short, simplistic definition may be used for students.

As part of navigating numerous external definitions, institutions must find ways to implement, synthesize, and communicate those definitions to different stakeholders. Furthermore, depending on the source and purpose of the definition, multiple institutional offices or departments may reference one or more of those definitions. For example, going back to the three ED definitions, the definition of 34 CFR 600.2 used for financial aid eligibility would most likely be referenced by instructional designers and faculty or compliance staff. The definition used at 34 CFR 668.8(m) used for accreditation review is most likely to be used by an accreditation liaison or institutional research or academic planning department. Meanwhile, the IPEDS definition is most likely to be used by institutional research or compliance staff.

What this does is decentralize the interpretations of these definitions, increase the number of individual interpretations, and increase the chances of misunderstanding or miscommunications. Furthermore, it becomes a balancing act for institutions to develop systems or institutional definitions to meet the needs of external stakeholders (i.e., regulators, accreditors) and institutional stakeholders, especially critically the needs of students.

For example, when ED began collecting distance education enrollment counts, WCET staff heard from institutional researchers confused by the IPEDS survey definitions. Some admitted that they reported the same enrollment numbers to the state, accrediting agency, and IPEDS, even though there were different thresholds as to which enrollments should be counted as distance education. Though there is risk in misreporting data, they ultimately decided that issues of institutional credibility and efficiency outweighed the risk. Collecting and reporting distance education enrollment data to align with multiple contradictory definitions would require multiple data fields, course codes, data analysts to run queries and ensure accuracy of the data reports, and IT staff time to develop the data fields and course codes. This may have worked its way out over time.

Furthermore, for institutions offering distance education outside of the institution’s home state, knowing where distance education is taking place is critical to out-of-state activity management and many compliance staff have developed procedures to ask students for their location at the time of enrollment. These procedures may or may not align with how exclusively distance education enrollment data is collected for IPEDS and it is very possible that those data could differ slightly. However, for expediency purposes, institutions that participate in state authorization reciprocity through the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (SARA) report IPEDS data to fulfill their SARA data reporting obligations.

There are reasons that different entities may have varying perspectives on how to define distance education in policy, but those differences can create contradictions that challenge institutions practically. For example, for purposes of Title IV eligibility, Congress and the ED felt it was important to distinguish between distance education and correspondence education. However, other organizations may not feel the need to distinguish between the two and may view them as falling into the same overall bucket in terms of modality. For example, the definition of online instruction in the District of Columbia incorporates the terms “Correspondence Course” and “Distance Learning” in its definition. Additionally, the Council on Social Work Education provides definitions of distance education generally but includes correspondence as a subcategory within that definition in policy.

Interinstitutional collaboration and agreement are important work. In the case of navigating these competing definitions, institutions should bring stakeholders together to weigh institutional risk and priorities, discuss ways in which the institution could operationalize or maximize administrative efficiencies, and reduce disparate or confusing messaging to students. Ensure course codes, course descriptions, and policy definitions are clear to students, so they know what they need to be successful in the course.

In developing definitions of distance education, it would be helpful to review and possibly reference already existing definitions. However, this should be done with caution to avoid interpretative differences.

In reviewing other sources of distance education definitions, a common theme was a reference back to and incorporation of one of the federal HEA and Title IV definitions. It is not surprising that institutional accreditors tend to cite or model distance education definitions in their own policies and procedures after one or more of HEA and Title IV definitions, since they must abide by certain federal provisions to maintain status as a Department-recognized accreditor.

Citing and referencing those provisions, as applicable, makes sense for consistency and clarity. These references also have the benefit of synthesizing the definitions used and minimizing variations in language. For any organization considering what definition of distance education to create or adopt, it would be helpful to review and possibly reference or adopt an existing definition from another entity. However, there is the potential for further confusion depending on how the definitions are cited and used.

However, an issue could arise when two agencies are interpreting the same language. This was recently observed with the interpretation of new requirements for “regular and substantive interaction.” WCET staff noted an interpretation of “direct instruction” to include asynchronous instruction by an accrediting agency and institutions informing faculty based on the accreditor’s language. An alternate interpretation by Department personnel was shared with WCET staff in a letter that is summarized in a previous blog post.

Conflicting interpretations could pose grave challenges when the institutional is subject to a financial aid review or audit.

When it comes to understanding policy, it is important for institutions to note that policies may be developed by a constituency with a different perspective and should note where a policy interpretation from one agency may differ from your own. Though the term “direct instruction” could reasonably be understood differently based on the audience and technical training of those doing such interpretation, it is important to be mindful of the interpretation and perspective of the agency that is enforcing the policy.

As reflected in the cited WCET-sponsored survey done by Bayview Analytics with analysis conducted by Nicole Johnson (Executive Director, Canadian Digital Learning Research Association), higher education has moved beyond distinct categories to a spectrum of use of digital technologies. And as summarized here in this post and in our new report, policy will not always fit practice and it will take a concerted efforts by institutions, and federal, state, and accrediting policies to ensure protection of students that are engaged in these technologies.

In the end, we have policies that are trying to delineate courses and programs into tight little packages with names. Unfortunately, digital and distance learning are now in a world where the use of educational technologies, synchronous meetings, and in-person sessions are on a spectrum lacking solid boundaries. We’re trying to harness the ocean, but the waves keep coming in.

We want to hear what further questions, issues, or considerations you have so that we can consider and address those questions in future research.

We look forward to your feedback and observations.