A new SARA (State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements) Policy Modification Process was approved by its oversight Board last summer. This new process will offer increased transparency and public participation in the development of SARA Policy additions and revisions to manage reciprocity for state approval of institutions offering distance education and select in-person activities across state lines.

We spoke with three members of the team that created the policy modification process. Each of these members communicated that the new policy increases transparency and engagement with everyone touched by reciprocity through SARA. In this post, we enthusiastically share this new process, its structure, and some specific directions for the public to be involved in the process.

Three Things You Need to Know Today:

- Reciprocity provides consistent student consumer protections for interstate distance education in all states that are members to the reciprocity agreement known as SARA.

- Public opportunity to participate in SARA policy modifications is through submission of proposals to modify policy and by providing public comment to the submitted proposals.

- Those interested in participation should carefully review and follow process steps and designated deadlines as found on the NC-SARA website: Overview of the SARA Policy Modification Process and 2023 Calendar.

Background on SARA and Its Policies

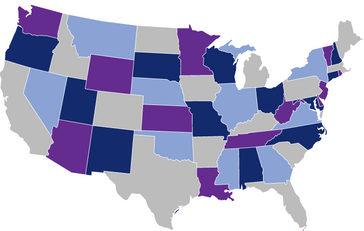

Beginning in 2014, states voluntarily began to join a state-to-state reciprocity agreement to address state authorization of institutions offering interstate distance education. SARA, as we now know the agreement, was developed to provide consistent state oversight of institutions by all member states. There is great concern regarding the wide variance of state-to-state requirements for institutional oversight nationwide that provides unbalanced consumer protection of students across the states. The SARA Agreement is a “negotiated compromise” of each state’s requirements for purposes of interstate distance education for postsecondary institutions.

Eight years later, forty-nine states, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, and District of Columbia have joined the reciprocity agreement. More than 2,300 institutions in those states and territories have obtained approval from their “Home State” to participate in reciprocity to obtain state institutional authorization to offer distance education related activities in other SARA states. However, despite the wide acceptance of SARA nationally, there remains confusion about some SARA requirements.

Additionally, some states and consumer protection advocates have shared an interest in enriched consumer protections which may be accomplished through revision in SARA policy. We anticipate that the new SARA Policy Modification Process will serve to alleviate confusion, clarify the role of the state, and provide increased student consumer protection.

“The new SARA policy modification process is intended to advance the purposes of state authorization and contribute to the success of students enrolled in programs covered under SARA. The process was designed to be as transparent and collaborative as possible and to give everyone who cares about these purposes the opportunity to meaningfully engage and contribute to them.”

– Sam Loftin, Director of Consumer Protection, Washington Student Achievement Council

SARA Policy Modification Process Development

Beginning January 2023, there will be increased opportunity for the public voice to be heard to improve upon SARA Policy to implement reciprocity. Not only will the public have the opportunity to submit proposals, but there will also be opportunity to provide public comments that will be made publicly available. This process offers the ability to enrich student consumer protections and clarify institution and state responsibilities.

As previously discussed, institution compliance requirements and the roles of all SARA stakeholders are provided in SARA Policy. Since the origination of SARA Policy, there has been a process for policy modification to address any changing needs of SARA stakeholders and to allow for the maturity of the reciprocity agreement. However, there had been some frustration with details within that process.

As a result, in the last year and a half, a collaborative group of representatives from each compact’s Regional Steering Committee developed a new proposed policy modification process. The process is intended to be more inclusive of the public, institutions, states, and regional compacts as well as provide transparency and open communication among all SARA stakeholders. By following the former policy to address modifications, the NC-SARA Board approved the new SARA Policy Modification Process in June 2022. The language can be found in the SARA Policy Manual Section 8.2: SARA Policy Modification Process.

The SARA policy modification process has been enhanced to prioritize member state voice, broad opportunity for input and feedback, transparency in developments throughout, and ultimately an annual pathway for thoughtful and consensus-based modifications to be achieved. SARA provides opportunities and options for students across the country, and the work continues every day to strengthen and enhance this impactful national network.

– Jared Abdirkin, Director, State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (SARA) New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE)

Modification Process

The policy review cycle will begin each January and will conclude with a final vote by the NC-SARA Board at the Fall NC-SARA Board meeting. The NC-SARA website will house the information for submission and review of proposal starting with the SARA Policy webpage.

Key process points and deadlines associated with the policy modification process are as follows:

- There is a 30-day window to submit proposals in the portal to be available on the NC-SARA website (Jan 3-Feb 3, 2023).

- All proposed policies will be published for public review.

- Parties offering policy proposals will have two different opportunities during the modification process calendar to present their proposal in a public forum.

- There will be a 30-day public comment period beginning April 17, 2023.

- There will be opportunities for parties submitting proposals to amend, revise, or withdraw their proposals per the timeline.

- Each of the four regional compacts will review and vote to approve or not approve the proposed policy modifications.

- Proposed policy modifications approved by each of the four regional compacts will be offered to the NC-SARA Board for a final vote at the Fall NC-SARA Board meeting.

- Policy modifications that are approved will be published in the amended SARA Policy Manual on December 1.

As mentioned, this is an annual policy cycle such that we anticipate that proposals that are not approved may be seen in an edited form in future cycles. Additionally, because this is the first year of this cycle, everyone will learn in this first cycle and implementation improvements will be considered in future years.

Policy Modification Submission Form & Communications

Proposals will be submitted by the specific Policy Modification Request Form that will be available on the Participate in SARA Policy Modifications webpage on the NC-SARA website. The standardized form will allow for collection of the necessary information in a uniform manner. The form will begin with fields for contact information to facilitate communication with the submitter. The submitter must also consider a concise naming of the subject of the request. Within the form there will be a field for the specific suggested policy language modification proposed and field to supply the rationale for this change. A submitter will find a link to the current SARA Policy Manual on the form. If the proposal is to revise a current policy, access to the manual will facilitate providing identification of the specific policy the submitter wishes to revise (ex. SARA Policy 5.2 Programs leading to Professional Licensure). Additionally, there will be the ability to share supporting documents if desired by the submitter. During a recent webinar, hosted by the NC-SARA office, it was explained that the form will provide for the opportunity to provide multiple proposals within one submission.

After the form is submitted, the submitter will receive a copy of the information submitted and instructions for logging in to make edits. The submitter will have two different opportunities to make edits to the proposal. Throughout the process submitters will receive automated communications to address key points in the policy modification process.

To facilitate public inclusion in this process, the public will have access to review all proposals. The proposals will be posted on the NC-SARA website no later than February 8, 2023, to give the public time for review in advance of the comment period in April.

The progress of the process may be followed by all interested parties by public announcements posted on the NC-SARA website and through public email to NC-SARA’s registered contacts. Interested parties that are not currently on the NC-SARA Mailing List will find access to register for the list at the footer of each webpage of the NC-SARA website under Stay Informed – Sign Up.

With the adoption of the new Policy Modification Process, the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (SARA) has been ushered into a new era. An era of clarity and transparency. An era of compromise. And most importantly, an era of genuine and effective collaboration. In a time when the foundational tenets of our nation are facing divisive rhetoric and immense polarization, concerned citizens set aside their differences and came together for a common cause…to protect students. This major milestone is proof that consensus can be achieved. Therefore, let us remember this achievement and allow the Policy Modification Process to guide our work as we continue to progress the state authorization reciprocity agreement.

– Terrence R. Scarborough, M.P.A.; Director of SARA North Carolina; Chair of the SREB-SARA Regional Steering Committee

Consider participating in the policy modification process!

Much like our encouragement to participate in the Federal rulemaking process by submitting public comments, we encourage you to follow the SARA policy modification process closely. Changes to SARA Policy could affect how you manage interstate compliance and provide support for your out-of-state distance education students. If you find areas of SARA policy confusing, you may wish to submit a policy proposal that provides clarification.

We anticipate that policies that had been paused during the modification process development will be revived and submitted through the new process. The Regional Steering Committee members have been active in working on proposals they will submit. Additionally, we anticipate that suggested enriched student protections suggested by consumer advocates will also be submitted.

Upon review of the published proposals of others, you may have questions, comments, and opinions about the proposed language, including ability to effectively implement the proposed policy, unintended consequences on students and questions about structure of the proposed policy. The public comment period in April is an important time for the public to raise their questions and concerns.

As we share about developing public comments for the U.S. Department of Education, we encourage you to be positive and helpful in your proposals and comments. It is important for us to remember that SARA Policy is intended to provide consistent regulatory oversight of institutions to protect students as consumers. Unfortunately, some think that making processes easier for institutions is the main purpose of SARA. While that is a nice side benefit, the state role in consumer protection is paramount in this state-to-state agreement. As a result, it is important to develop clear and reasonable policies for which the institution can implement to best serve their students.

The recent webinar, The SARA Policy Modification Process hosted by NC-SARA is posted on the NC-SARA website for your review. We urge you to review their archived recording and slide deck.

Watch for SAN and WCET to share more on the progress of this new process. Look for the opportunity to submit a proposal in January. Then in April, look for the opportunity to review and submit public comments to address any clarification, guidance, or concerns that you may have about the proposed policies. We are excited about the potential of this new process and look forward to reporting on the next steps!