While it seems we have an increasing number of options when it comes to virtual services and activities – anything from banking, to food delivery to scavenger hunts – the virtual world can be lacking when it comes to social interaction. This is an important challenge for higher education institutions offering partial or fully online courses.

This is why we’re thrilled to learn about virtual community strategies from Nicole Barbaro, College Innovation Network at WGU Labs, and Janelle Elias, Rio Salado College. Nicole and Janelle highlight how Rio faced the above-mentioned challenge and how their solution benefits their students. Thank you Nicole and Janelle!

Enjoy the read,

– Lindsey Downs, WCET

Online higher education is becoming increasingly common and more widely accepted, in large part due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that in 2020, 75% students enrolled in at least one online course in college, and 44% of students were enrolled exclusively in online courses – increases of 97% and 186% compared to 2019, respectively.

While online education offers greater flexibility and broader accessibility for students, there is an important trade-off: students may be missing out on the social learning experiences that are inherent to in-person learning.

The importance of the social side to higher education for students was highlighted as a result of the near universal shift to online learning that began in 2020. A 2021 Inside Higher Ed survey showed that 71% of students report that the lack of connection with peers and faculty is a significant challenge posed by online learning. Similar results were found by a 2021 College Innovation Network survey that showed 69% of students feel less connected to their peers in online learning environments.

Building RioConnect at Rio Salado College

Given the importance of peer community and belonging for student success, it’s vital that online education creates new ways for students to connect. This means building what are referred to as “virtual communities” that give students a dedicated space to learn from others, get support, socialize, and boost belonging.

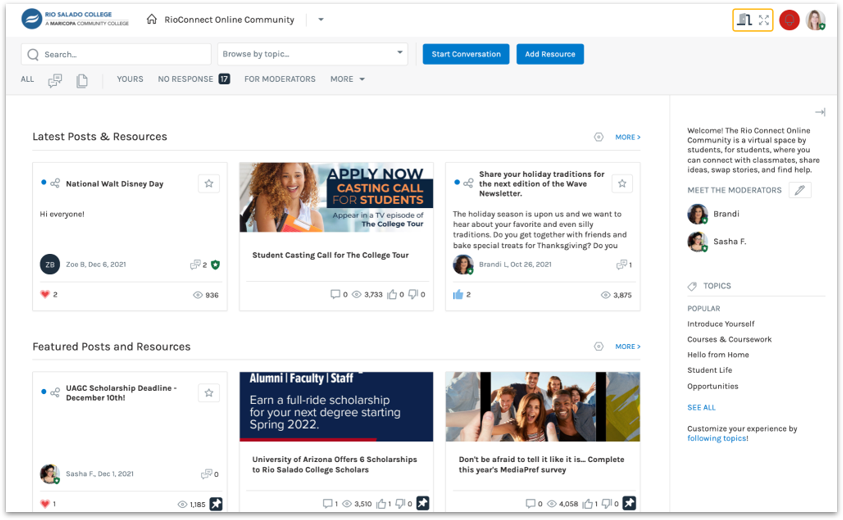

A nice case study of the impact that virtual communities can have on students is the recently launched RioConnect community (powered by InScribe) at Rio Salado College – a primarily online community college in Tempe, Arizona.

In our research, we followed over 200 Rio Salado students across six weeks to evaluate how engaging (or not) with the virtual RioConnect community changed their sense of belongingness and peer connectedness.

What we found was encouraging:

- Students who engaged with the virtual community had a significantly higher reported sense of belonging and peer connectedness compared to students who did not participate.

- Over the six-week study period, engaging in the community was associated with an increase in belonging and connectedness for students. In fact, one student shared that “we now have engagement with other students so online learning doesn’t feel so isolated.”

It’s clear that virtual communities are an effective way for online students to get to know each other and promote belonging, but how can college leaders get it right? Throughout the process of building the RioConnect community and working with the student users, we’ve learned a few things that college leaders should know about building online communities.

1 – Make the space “for and by students”

It takes more than deciding to make a space for students, but to ensure that the space is really what students want and need (see next point), the virtual community must also be created by students. When building RioConnect, student leaders were recruited to be part of the team.

By involving students in the community creation and getting conversations off the ground, it fostered the sense of a true student space that felt comfortable to participate in, and the leaders set a positive example of engagement for other students, in addition to encouraging participation from other students.

2 – Students want value-add

By involving students in the building of the community, the space is more likely to provide what students really need –

support, connection, and information.

Students have a lot of responsibilities and commitments, so it’s vital that a new tool and space offers clear value for students. By involving students in the building of the community, the space is more likely to provide what students really need – support, connection, and information.

The value-add came through in our research when speaking with students. As one student shared, “I like that the forum provides a general space for questions, strategy, and peer-offered assistance.” Students also desire practical information about classes, too, as another student said, “I think the discussions that start up on RioConnect are very interesting and provide good advice on future classes I may take.”

3 – Virtual spaces are more inclusive

Online learning offers flexibility for many, but the shift to online has been particularly beneficial for increasing inclusivity for all students. In-person networking and social clubs are a staple of college, but online options allow for a greater range of engagement that make many students more comfortable socially. As one student shared, “I like that you can choose whether or not you want to feel included and it doesn’t have to be in person because I have social anxiety.”

4 – Continue to iterate

A community takes nurturing and development. And within higher education, students’ needs are continuously changing and evolving. Your virtual community must evolve, too! Iteration can be achieved in a couple ways. One is to do continuous research to ensure the community has the desired impact over time, and to gather formal feedback from users. Another strategy is to have a student committee to ensure a continuous pulse on the needs of the student community. Belonging is an ongoing process – be sure to integrate checks into your strategy to keep the community vibrant.

Virtual communities are a great way to engage online students and help boost belonging at your institution. With online and tech-enabled learning becoming more ubiquitous in higher ed, our collective learnings and lessons will help ensure that our online students stay socially connected and supported in their peer communities.