In this second of our blogs dedicated to exploring the outcomes of the recent negotiated rulemaking sessions, Cheryl Dowd and Russ Poulin focus on the state authorization for distance education language that transpired from those conversations. They also share some integral changes to professional licensure notifications, as those requirements have been expanded to ALL programs — both distance education and face-to-face.. Enjoy!

–Erin Walton, contract editor for WCET

Despite the flowers, birds, and hints at warmer temperatures, we are continuing in Federal Regulations Groundhog Day for state authorization. The outcome of the 2019 Negotiated Rulemaking may be a positive move to break this almost ten-year loop with a Federal regulation that may become effective July 1, 2020.

You may recall that last May, in a post inspired by the famous movie starring Bill Murray, we shared the long history of the attempts to provide an enforceable Federal state authorization regulation that ties institutional compliance with state laws to the ability of the institution to participate in Title IV federal financial aid programs. Last May, we reported that the Department of Education was proposing to delay the 2016 Federal regulations for State Authorization of Distance Education that were to be effective July 1, 2018. Since that time, there has been an official delay, lawsuits (disputing the legality of the delay), and negotiated rulemaking. Oh my!

In this second in a series of posts on the most recent negotiated rulemaking process, we focus on the state authorization for distance education language that emerged from those sessions. We also highlight a very big change to disclosures to students in programs leading to professional licensure or certification by a State. Those notifications will now apply to both distance and face-to-face students who are on-campus.

RECAP

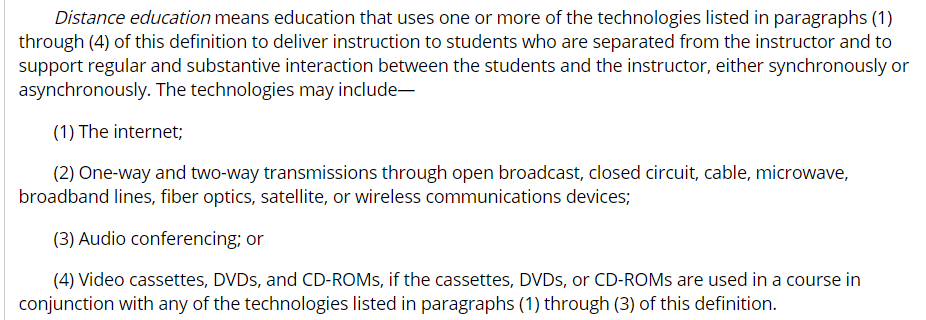

The latest chapter in this saga began on July 3, 2018. At that time, the Department of Education officially announced a delay of most of the 2016 Federal regulations for State Authorization of Postsecondary Distance Education, Foreign Locations. Their plan was to delay implementation of and to review and revise the following regulations:

- 34 CFR 600.2: Definitions – State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement.

- 34 600.9 (c): State authorization and process for review.

- 34 668.50: Institutional Disclosures for programs completed solely through distance education (excluding internships and practice).

Of the new regulations that were to go into effect on July 1, 2018, only Federal regulation 34 CFR 600.9(d) regarding state authorization in foreign locations continued and was not subject to the delay. However, because the Department posted the announcement after it was supposed to go into effect, there is a lawsuit disputing the legality of that delay. But, that is another story.

August 2018 brought news of a proposed negotiated rulemaking plan to include state authorization plus many other issues related to accreditation and education innovations. The Department moved forward with the Negotiated rulemaking committee hearings in January with an unprecedented rulemaking management plan. Despite many naysayers, including WCET and SAN staff and members who thought that a negotiated rulemaking plan with such a wide-ranging set of issues could not possibly result in overall agreement, consensus was reached on April 3, 2019.

RULEMAKING FOR STATE AUTHORIZATION

The issue of state authorization was among the many issues delegated to the Distance Learning and Educational Innovation subcommittee to research, discuss, and advise the main negotiated rulemaking committee. The subcommittee began its discussions of most issues by review of the Department’s initial proposed language. It should be noted that, for the issue of State Authorization, the Department proposed complete removal of the federal regulations. Subcommittee members raised the fact that state regulations remain in place regardless of a federal state authorization requirement. Many also said that it makes sense to tie institutional eligibility to disburse federal financial aid to adherence to state laws. As a result, the subcommittee was virtually unanimous in its agreement to retain some portion of the rules. The Department was open-minded to discussion and changes to the Department’s initial proposed language.

The subcommittee was not required to meet “consensus,” which is complete agreement on all issues. However, the vast majority of the subcommittee agreed upon language to share with the main committee. A few members wished to see greater limits on reciprocity agreements, and those concerns were also shared as part of the subcommittee’s report.

The main committee addressed state authorization in the final days of rulemaking. It became apparent that the issue was more complicated than anticipated, which raised frustration to understand the issue and develop solutions.

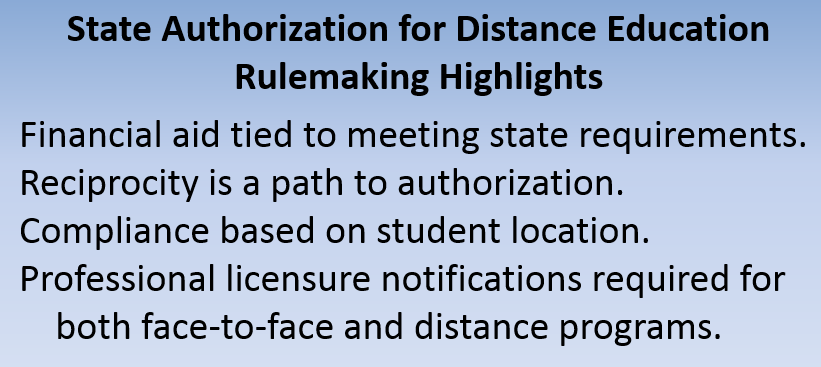

Ultimately, despite consumer protection concerns about removal or non-removal of institutional disclosures and the difference between defining reciprocity versus attempting to direct a non-governmental organization that facilitates reciprocity through state government choice, state authorization related regulations were part of the consensus package. Key components of the consensus regulations include:

- Eligibility to disburse Title IV aid is tied to institutional approval demonstrated by:

- Direct approval by the state; or

- Through a state authorization reciprocity agreement.

- Authorization is based upon the location of the student:

- The institution needs a “defensible” (our word) process; and

- Student location is determined at enrollment or when the student reports that his or her location has changed.

- State Authorization reciprocity agreement definition:

- Returns to the language provided in the 2016 regulations.

- An agreement between states that allows institutions to provide educational activities in other states as directed by the agreement.

- Disclosures

- 34 CFR 668.50 was removed as most disclosures were already required elsewhere in the Federal Code. Since the entire institution is required to make many of these disclosures, it was thought unnecessary to have special requirements for distance education.

- Professional Licensure Notifications moved to 34 CFR 668.43(a) now general and direct notifications required for all programs regardless of modality.

In this section, we describe our best understanding of the main elements of the proposed requirements for state authorization for distance education.

Federal Financial Aid is Tied to the Institution Being in Compliance with State Rules

The essence of the revised language indicates that, for an institution to offer Title IV financial aid, the institution must meet the requirements of the State in which the student is located. Upon request, the institution must show proof of compliance to the Department. If the institution offers postsecondary education through distance education or correspondence courses to students located in a State in which the institution is not physically located or in which the institution is otherwise subject to that State’s jurisdiction as determined by that State, then the institution is subject to the State’s jurisdiction, as determined by the State.

There are two options for demonstrating compliance in a State:

- Evidence of compliance directly through the State or

- By participation in a reciprocity agreement for state authorization.

Compliance is Based on Student Location

The issue of “location” versus “residence” was a very important issue to clarify during rulemaking, as this was quite confusing in the delayed language that was to go into effect last year. You may recall WCET , NC-SARA, and DEAC raised this concern and asked for a clarification from the Department to be consistent with State oversight of activity that occurs in the State. It was explained that the term “residence” relates to where the student may vote or hold a driver’s license but may not be where the student is “located” when participating in the activity provided by the institution.

It is important to remember that the legal jurisdiction for state actions is based on the location of the student and NOT the official residence. Therefore, any federal requirements basing financial aid on compliance with a State need to be in harmony with those state rules. We appreciated that the negotiators came to understand this important distinction between “location” and “residence.”

How to Determine Student Location

There was much discussion of how and when institutions should determine a student’s location, and there was some interest in having very specific requirements. Since institutions already use different processes, it was decided to allow for institutions to use those different practices as long as they meet some criteria.

Location of the student is defined as being determined in accordance with a consistent practice of the institutions policies. The regulation indicates the institution must describe the policy upon request. Additionally, the institution’s determination of location is made at the time of enrollment and, if applicable, when there is a formal receipt of a change through institutional procedures. Our (unofficial) thoughts of examples include: change of address requests, affiliation agreements for clinical placements, proctor requests, internship registration processes, or registration processes developed by the institution.

What is being proposed echoes what WCET and SAN staff have described in the past as a “defensible” process. That is, a process that is written, applied consistently, and that would meet the external scrutiny of state oversight, federal auditors, or lawsuits. Again, that is our interpretation, and we will need to await more specific guidance from the Department.

This was an incredibly difficult issue to manage as the negotiators moved through confusion about developing a definition of reciprocity versus placing requirements or parameters on NC-SARA, which is a current non-governmental organization that is facilitating reciprocity through independent and voluntary participation by states. Some thought that the states had “outsourced” oversight to SARA, which is not the case. As a state-to-state agreement, each state still is responsible for enforcement, but uses the standards that their governors and legislators have agreed upon through joining the agreement.

Coming to a Compromise

Negotiators attempted to develop a compromise on additional requirements for reciprocity agreements. After those discussions, one representative seemed to surprise many other members by introducing a new proposal that included additional restrictions on reciprocity than those that were inspired by a desire to change NC-SARA. These newly proposed rules were stricter than those previously presented and were rejected by most members of the subcommittee. The consumer protection representatives had sought to allow states to treat for-profit institutions differently in reciprocity. The newly proposed language would allow states to deny reciprocity to any institution. In our opinion, that language would have negated reciprocity.

Unable to come to agreement on newly proposed language defining a reciprocity agreement, the negotiators reached a compromise by reverting back to the 2016 Federal regulation language. The language from 2016 simply states that a state authorization reciprocity agreement is an agreement between states to provide educational activities in the other participating states as directed by the agreement.

Negotiators knew that they were very close to coming to “consensus” on the entire package of proposed regulations. Since “consensus” means agreement on all issues, they did not want this one issue to bring down the work that had been accomplished on all the other issues.

The Problems with What We Are Calling the “Ted Mitchell” Compromise

In 2016, WCET and NC-SARA sought clarification about the last phrase of the definition indicating that the agreement “does not prohibit a state in the agreement from enforcing its own statutes and regulations whether general or specifically directed at all or a subgroup of educational institution.” The concern was a state choosing to impose its own statutes and regulations that could conflict with processes created and agreed by the state to participate in the reciprocity agreement.

In response to a request for clarification from WCET, SAN, and NC-SARA, during the waning hours of the Obama administration, Department of Education Under Secretary of Education, Ted Mitchell responded in support of reciprocity and stated:

“In other words, a distance education reciprocity agreement may require a State to meet requirements and terms of that agreement in order for the State to participate in that agreement.”

Therefore, states agreeing to participate in the reciprocity agreement must follow the requirements and terms of the agreement if they intend to participate in that agreement.

During the 2019 rulemaking, the Department indicated that they were aware of the letter and supported Ted Mitchell’s opinion in what we have called the “Ted Mitchell Compromise.” Frontiers posts during January 2017 more fully describe the Ted Mitchell’s response and also the communications related to clarification from the Department to Russ Poulin.

We note that Ted Mitchell’s letter does not hold the weight of being an official interpretation as they ran out of time to issue a “Dear Colleague” letter. We believe the Department will uphold that interpretation; others will vigorously dispute that interpretation.

At the NASASP’S conference on Monday, Diane Auer Jones, Principal Deputy Under Secretary of the U.S. Department of Education, said that this issue is up to the states and did not see the federal government getting involved. The interpretation of the reciprocity definition will be a big issue in the coming year.

A Convening Regarding NC-SARA Was Another Element of the Compromise

There was significant conversation around the notion that states are sovereign entities that chose to join the current organization facilitating reciprocity, which is not under the direct purview of the Department. During the end of negotiations on this topic area, negotiator David Tandberg, Vice President of Policy Research and Strategic Initiatives at SHEEO, offered to co-host a “convening” with fellow negotiator, Terry Hartle, from the American Council on Education, to invite members from the Department, veterans, students, states, consumer advocates, and NC-SARA to discuss consumer protection concerns with NC-SARA. This convening is specific to working with NC-SARA on the subject of reciprocity, not intended to be a review of the general rule of state authorization. It is hoped that some of the concerns with NC-SARA can be resolved by beginning a dialogue.

The 2016 Federal Regulations included a section specifically for disclosures for distance education programs (34 CFR 668.50). There were approximately six or so different Public Disclosures required including complaints, refunds, adverse actions, and prerequisites for professional licensure. Direct disclosures were also required under certain circumstances. This section has been completely removed.

However, it was determined that many of these disclosures are already required by other Federal regulations (ex. Complaints: 34 CFR 668.43(b) & Refund Policies: 34 CFR 668.43 (a)(2)). Although we know that it is important to provide professional licensure disclosures to comply with Federal Misrepresentation regulations, the negotiators agreed to create a specific listing within the Federal regulation for Institutional Information to provide the professional licensure disclosures.

The essential components of this new Professional Licensure disclosure regulation are described below.

General Disclosures whether completion of a program is sufficient to meet licensure requirements in a state for that occupation.

General disclosures are typically provided to students via the institution’s website, and the requirements include:

- The program is designed to meet educational requirements for professional license or certification required for employment in an occupation or advertised as meeting requirements.

- This requirement is for BOTH face-to-face and distance education students. (Note: This is a major change from previous language.)

- Available to enrolled and prospective students.

- Institution must indicate one of the following – website would be acceptable:

- States curriculum meets education requirements.

- States which the institution determines the curriculum does not meet educational requirements.

- States which the institution has not made a determination.

Direct Disclosures to a student in writing which may include email or other electronic communication.

Direct disclosures are typically provided to students via electronic communications sent specifically to each affected student, and the requirements include:

- Students must receive a direct disclosure:

- If the institution has already determined that it does not meet educational requirements, or it is undetermined in the state where the prospective student is located.

- If the institution subsequently determines that the program does not meet requirements in a state where the student is located, the institution must provide notice within 14 days of making the determination.

- These disclosures are to be made to both face-to-face and distance education students.

- These disclosures are to be made to both enrolled and prospective students.

- Upon request, the institution must provide the Secretary with written documentation of the basis for determination of the student’s location.

- A determination of the student’s location at the time of student’s initial enrollment and, if applicable, upon knowledge of change of location of state through an institution process.

Ultimately, it was determined by the negotiators that it is imperative that students should be advised by institutions whether the program the student wishes to pursue will provide him or her with the educational prerequisites to seek licensure or certification at that location.

As we have shared before, with the additional marketing and opportunities for nationwide online learning, a student would naturally be challenged to understand why an institution would offer programs in his or her state that would not meet educational requirements for licensure and certification. WCET and SAN have consistently advised institutions to work collaboratively with the academic programs at the institution to research prerequisites in states the institution would like to seek students. The institution is not under any obligation to offer all programs in all states, but must communicate effectively with both current and prospective students.

CONCLUSION AND TIMELINE

It must be noted that there has been considerable criticism of the negotiated rulemaking process. There were underlying realities that were ignored or downplayed in the press in the attention to dissenting voice. We would like to highlight the following:

- The Department Listened. It was thought, even by us, that since the Department was going to come to the table with proposed language, that they would not want to divert from what they proposed given the short timeline. On state authorization, the Department staff listened intently to the subcommittee and performed a complete 180 degree turn. They chose a direction that protected students and honored the State’s role. The Department staff who have worked on the rulemaking deserve credit.

- Higher Ed Asked for More Regulation. There have also been claims that the rulemaking committees were tainted because they were representing the higher education hierarchy. On state authorization, they chose to regulate themselves. The negotiators also deserve some credit.

- Consensus is Rare. Coming to complete consensus was an extraordinary feat. For state authorization, we are left with a reciprocity agreement definition that will remain controversial for some time. But, everyone should remember that no one got everything they wanted. That is the reality of negotiations and compromise.

For state authorization, it appears as though the negotiators were able to address most of the questions that WCET and SAN have raised since the 2016 Federal Regulations were proposed. Still, some questions remain.

Maybe the Federal Regulations Groundhog did not see his shadow this time, meaning that actual enforceable regulations will finally be on the horizon! Is it perfect? Is it easy to comply? Of course, the answer is no. But… most of the pieces are moving in the right direction to help and protect students, provide a reasonable process for institutions to responsibly offer their programs beyond their state, and give regulators reasonable procedures to provide oversight of program offerings.

Maybe the Federal Regulations Groundhog did not see his shadow this time, meaning that actual enforceable regulations will finally be on the horizon! Is it perfect? Is it easy to comply? Of course, the answer is no. But… most of the pieces are moving in the right direction to help and protect students, provide a reasonable process for institutions to responsibly offer their programs beyond their state, and give regulators reasonable procedures to provide oversight of program offerings.

Timeline:

- The Department is reviewing the language approved by the committee for spelling, grammar, formatting, and adherence to existing statutes.

- The Department will release proposed regulations in the next several months.

- The public will be asked to provide comment on the proposed regulations. Note: We will need your help in the comment period!!

- The Department will review the feedback on the regulations.

- October 1-2, 2019 – State Authorization Network Advanced Topics Workshop: Update on HEA & Federal Rulemaking: The Impact on Institutional Compliance.

- A release of final regulations by November 1, 2019 will cause a July 1, 2020 effective date for the final regulations.

- The Department indicated that the earliest rules will go into effect July 2020, but the implementation process could go into 2021.

Whatever happens, you know that WCET and SAN will continue to provide guidance in preparation for institutional compliance for July 1, 2020…or whenever the Groundhog reappears.

Cheryl Dowd

Director, State Authorization Network

WCET – the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies

cdowd@wiche.edu

Russ Poulin

Senior Director – Policy, Analysis, and Strategic Alliances

WCET – the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies

rpoulin@wiche.edu

Its use is spreading widely and, at

Its use is spreading widely and, at

When learning to care for patients who are calling in from remote locations, students are taught to ask, “Are you in a secure place? Are you in a place where we can talk confidentially?” Even if the patient can’t talk out loud, a secure conversation may be possible via texting. Practicing scenarios like these can help future healthcare providers keep a level head when treating telehealth patients in emergency situations.

When learning to care for patients who are calling in from remote locations, students are taught to ask, “Are you in a secure place? Are you in a place where we can talk confidentially?” Even if the patient can’t talk out loud, a secure conversation may be possible via texting. Practicing scenarios like these can help future healthcare providers keep a level head when treating telehealth patients in emergency situations.

ons, accreditors are required to secure evidence of effective practice in the form of a secure login and pass code; proctored exam; or other technologies and practices that are effective in verifying student identity. The revision calls for accreditors to require institutions to have processes in place through which the institution establishes that the student who registers in any course offered via distance education or correspondence is the same student who academically engages in the course or program. Securing evidence of robust student identity verification practices needs to remain a key feature of distance education quality assurance. Evidence of effective student identity verification supports evidence of student achievement. (See additional comments in the last section below).

ons, accreditors are required to secure evidence of effective practice in the form of a secure login and pass code; proctored exam; or other technologies and practices that are effective in verifying student identity. The revision calls for accreditors to require institutions to have processes in place through which the institution establishes that the student who registers in any course offered via distance education or correspondence is the same student who academically engages in the course or program. Securing evidence of robust student identity verification practices needs to remain a key feature of distance education quality assurance. Evidence of effective student identity verification supports evidence of student achievement. (See additional comments in the last section below). Finally, it is interesting to note some changes from previous iterations (

Finally, it is interesting to note some changes from previous iterations (

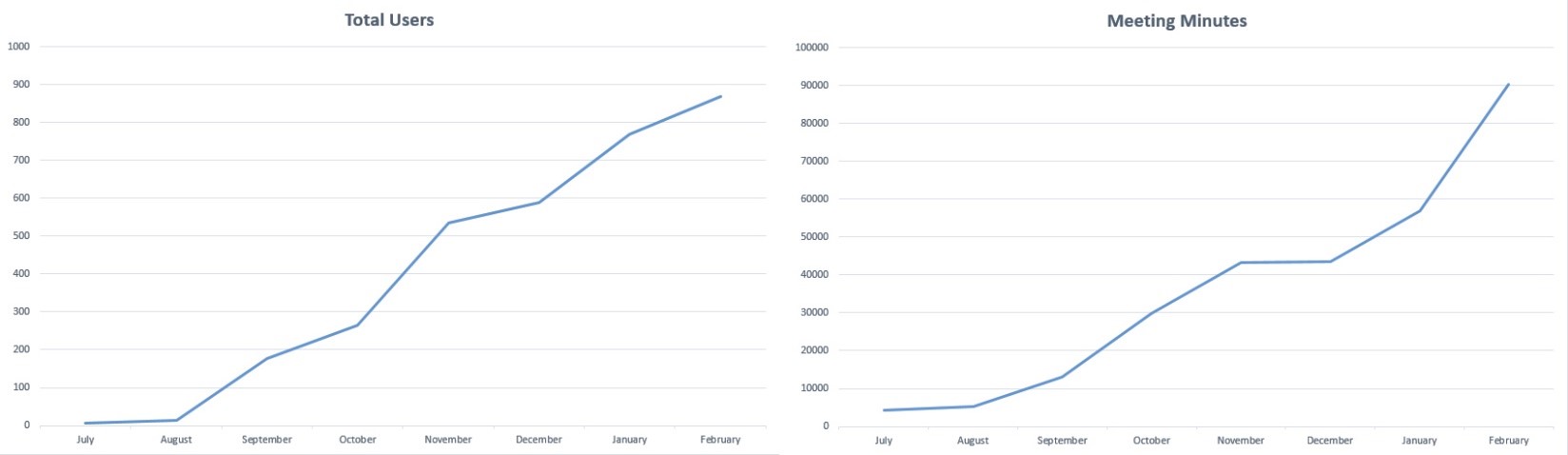

As a district, we recognized what was happening and listened to their needs. However, we did not want to rush into a mass implementation of a product just because some of our colleges were utilizing it. We wanted to see if other solutions on the market provided better alternatives to what was currently being piloted.

As a district, we recognized what was happening and listened to their needs. However, we did not want to rush into a mass implementation of a product just because some of our colleges were utilizing it. We wanted to see if other solutions on the market provided better alternatives to what was currently being piloted.

Just two weeks ago, we reported that we thought that maybe we were seeing the

Just two weeks ago, we reported that we thought that maybe we were seeing the  What appears to have been missed here is that the essence of the delay was the confusion about proper institutional implementation.

What appears to have been missed here is that the essence of the delay was the confusion about proper institutional implementation.  Given the difference in the requirements, does it make sense to enforce unclear rules with one set of requirements when a new set of rules will likely be in place a year later? The likelihood is chaos for the institutions to implement processes to both comply with the 2016 regulations and put in place processes to be in compliance for July 1, 2020.

Given the difference in the requirements, does it make sense to enforce unclear rules with one set of requirements when a new set of rules will likely be in place a year later? The likelihood is chaos for the institutions to implement processes to both comply with the 2016 regulations and put in place processes to be in compliance for July 1, 2020.

Across the globe, institutions are embracing the core of Clayton Christensen’s notion of “

Across the globe, institutions are embracing the core of Clayton Christensen’s notion of “

Maybe the Federal Regulations Groundhog did not see his shadow this time, meaning that actual enforceable regulations will finally be on the horizon! Is it perfect? Is it easy to comply? Of course, the answer is no. But… most of the pieces are moving in the right direction to help and protect students, provide a reasonable process for institutions to responsibly offer their programs beyond their state, and give regulators reasonable procedures to provide oversight of program offerings.

Maybe the Federal Regulations Groundhog did not see his shadow this time, meaning that actual enforceable regulations will finally be on the horizon! Is it perfect? Is it easy to comply? Of course, the answer is no. But… most of the pieces are moving in the right direction to help and protect students, provide a reasonable process for institutions to responsibly offer their programs beyond their state, and give regulators reasonable procedures to provide oversight of program offerings.