I have always enjoyed the “Spy vs. Spy” section of Mad Magazine. If you are not familiar with it check out this animated version. In the wordless comic strip two spies battle it out against each other. The spies are identical except for one is dressed in black and the other in white. The comic strip is entertaining because every time one spy is confident that he has foiled the plans of the other spy some new technique or technology will be introduced to reverse the outcome.

Technology Can Enable Learning (and Cheating Too)

Technology Can Enable Learning (and Cheating Too)

Those of us in the industry of exam proctoring can identify with this. Just when we get good at preventing cheating with one strategy, the students come up with another strategy. Once it was sufficient to not allow students to have their cell phones with them during testing. But now there are various forms of wearable technology that can be used to cheat. Sometimes it seems that even our best efforts only serve to keep the honest students honest. When a student is intent on cheating, they often seem to find a new way.

Just as technology can be a great tool for learning, it can be an effective tool for cheating as well. Some of the ways that students have indicated that they cheat include texting answers to other students during an exam, snapping pictures of an exam using their phone, using their phone to search the Internet for answers during an exam, purchasing term papers online, and creating fake test scores or letters of recommendation for college admission.

Many Students Admit to Cheating

The Josephson Institute on Ethics surveyed 23,000 American high school and college students about their frequency and perception of cheating. More than half (51%) admitted to cheating on an exam one or more times in the past academic year. Students were asked if they agreed with this statement, “In the real world, successful people do what they have to do to win, even if others consider it cheating.” Fifty-seven percent of students agreed.

When asked by the Josephson Institute why they cheat, the leading responses included – peer pressure, to help a friend, the gains outweigh the penalties, low chances of being caught, pressure from expectations, and not enough time to prepare. As we prepare learners to be competent professionals in their careers, one very important aspect is to instill in them a mindset of integrity. To foster this culture of integrity, schools are using services that authenticate learner identity and monitor student performance during examinations.

Survey on Test Proctoring Perceptions

To contribute to the body of knowledge about academic integrity SmarterServices administers the Annual Proctoring & Learner Authentication Survey. The purpose of the survey is to collect data about good practices and perceptions using learner authentication and testing integrity services. While the Josephson Institute survey and others have focused on the event of cheating, this survey focuses on efforts to monitor student behavior in an effort to discourage cheating.

Responses were received from 365 persons representing the following stakeholder groups: Faculty (21%), Learners (15%), School Administrators (20%), Proctors (12%) and Test Center Administrators (32%).

The following findings from the survey are relevant to current practice:

- The four most common proctoring modalities reported by faculty and school administrators are an approved human proctor (HR Director, School Principal, Librarian, Notary, etc.), local test centers, instructor as proctor, and live-virtual proctoring.

- Faculty are most satisfied when they proctor their own exams or use a corporate testing center, and faculty reported the lowest level of satisfaction with automated virtual proctoring.

- Faculty perceived an instructor proctored exam as being the strongest psychological deterrent to cheating and virtual proctoring as the weakest.

- The proctoring modality which students perceived to be the strongest form of psychological deterrent was an approved human proctor. Automated, virtual proctoring was perceived as the weakest form of psychological deterrent. It is not surprising that students reported that their preferred proctoring modality was automated virtual proctoring. Students also reported that the proctoring modality in which it would be the most difficult to cheat is instructor as proctor.

- Students rated comfort and convenience as much stronger factors in their decision about a proctoring modality than cost.

Complete survey results are available on our website.

How Can We Foster Academic Integrity?

So what can be done to foster a culture that promotes academic integrity? I have had several conversations recently with faculty and proctors about the matter. Here are some actionable suggestions from those conversations:

CURRENT TECHNOLOGY – Rest assured that students will take advantage of the latest technology in their efforts to cheat. Faculty and proctors must stay informed about emerging technologies and their impact on testing integrity.

HONOR CODE – Each educational institution which measures mastery through assessment should issue an honor code to their students so that the students understand the expectations relative to academic integrity. One of the most common excuses that students make when confronted with a testing integrity violation is that “no one told me that doing this was wrong.” Students must understand how they should act with honor and integrity as well as the rules of what is and is not allowed. A part of the honor code should be the ramifications and punishments for violations.

INTEGRITY TRAINING – Students have differing perceptions about which behaviors are acceptable. A training program should affirm and encourage those actions which are honorable and inform students about the actions that are not honorable and the ramifications both professionally and academically. Orientation courses or new student experiences are great places for such training. Some faculty members have students sign an integrity statement as an early assignment in their course.

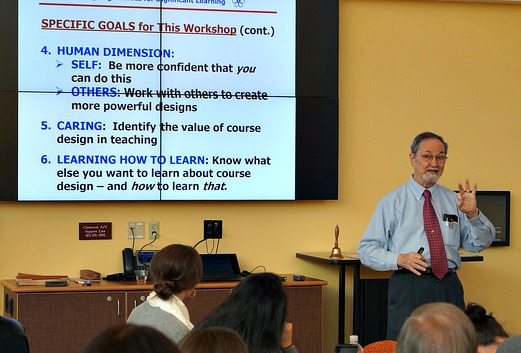

FACULTY INVOLVEMENT – When a faculty member is actively engaged in a course then the student is more likely to feel that cheating is a violation of that relationship. When an online course is taught in a fully automated fashion then the human element is removed and the student may feel that that they are not letting any particular person down if they cheat.

MULTI-MODAL APPROACH – Just like the spies, when students take all of their exams in the same context, they will begin to notice weaknesses and attempt to exploit them. It is a good practice for a school to provide several modalities of proctoring and not allow students to do all of their testing with one modality. Examples of testing modalities include – instructor as proctor, testing in a testing center, testing with an approved proctoring professional (I.e. a human resources officer in a corporation), automated-virtual proctoring, and live-virtual proctoring. Tools such as SmarterProctoring.com facilitate the work flow management in a multi-modal environment.

If you have ideas, war stories or success stories about fostering a climate of academic integrity, I would like to hear from you.

Dr. Mac Adkins

CEO and Founder

SmarterServices.com

mac@smarterservices.com

Photo Credit: ini budi setiawan

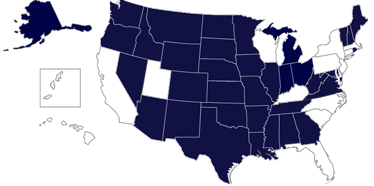

Over the last few years, I’ve had positively wonderful experiences within the world of state authorization – experiences that have changed me as a professional and as an individual. I have had the distinct honor and privilege to work alongside some of the most dedicated, smart, tenacious, and fearless professionals I’ve ever known. I attribute my growth and willingness to step outside my comfort zones to my incredible friends and colleagues.

Over the last few years, I’ve had positively wonderful experiences within the world of state authorization – experiences that have changed me as a professional and as an individual. I have had the distinct honor and privilege to work alongside some of the most dedicated, smart, tenacious, and fearless professionals I’ve ever known. I attribute my growth and willingness to step outside my comfort zones to my incredible friends and colleagues. State authorization can be some of the most frustrating, nuanced, complex, exciting, and layered work one can do in his or her professional career. It demands a vast array of skills and competencies, challenges our expectations, and pushes us to solve problems in creative ways. Our long-running joke about “it depends” succinctly describes the overt ambiguity we deal with on a daily basis and underscores the need for patience and constant diligence.

State authorization can be some of the most frustrating, nuanced, complex, exciting, and layered work one can do in his or her professional career. It demands a vast array of skills and competencies, challenges our expectations, and pushes us to solve problems in creative ways. Our long-running joke about “it depends” succinctly describes the overt ambiguity we deal with on a daily basis and underscores the need for patience and constant diligence. Leaders function to drive ideas and provide information so others can make informed decisions. And although you may believe you are not in a clear leadership role, you are in essence providing leadership and performing a valuable service for your institution. At the end of the day, adopting a leadership mindset can help overcome obstacles and provide opportunities to benefit your institution and students.

Leaders function to drive ideas and provide information so others can make informed decisions. And although you may believe you are not in a clear leadership role, you are in essence providing leadership and performing a valuable service for your institution. At the end of the day, adopting a leadership mindset can help overcome obstacles and provide opportunities to benefit your institution and students. Jason Piatt

Jason Piatt