Note: This blog post is for those managers of online learning or extended learning units who are in maturing organizations. If you have started an online learning unit or recently been asked to transition an operation to partially or fully self-supporting and are experiencing growing pains in more than one way, this article was written for you.

In terms of online operations, we are fortunate that we have some very good models from which to model part or all of our organizational structures. We have national quality standards that we can choose to adopt, budding research to point to the successes and challenges in our field, and a strong group of national organizations to help us learn more and remain engaged. Depending on the size of your institution and the scope of your role, some aspects of moving the innovation dial may be easier than others. Yet, as a leader of online learning on your campus, you have the responsibility for applying your knowledge to advance your institution’s mission.

For many years, I have been reflecting on my own successes and deficiencies with leading a maturing online learning department at a selective admissions research university with high research activity. When I was recently asked to transition my Office into a fully self-sustaining unit within two years, my need for reflection intensified.

Below are a few tips from what I learned through five years of leading a new and now maturing Office of Distance Learning. If I am honest with you and myself, I learned some of these lessons through trial and error or from just making a mistake. Either way, my hope is that these tips and kind suggestions will enable or embolden you in some way on your journey to sustaining innovation.

Acquire Talent.

Your success will depend on how well you can acquire the talent you need. First, you must make your case to the decision makers about why the positions are needed and show your vision for maximizing your human resources. Honor the investments by hiring right. Don’t rush the process. I suggest using a four phase process where you involve your current staff in reviewing applicants, conducting phone interviews with your staff and candidates you are interested learning more about, having the top performers participate in responding to a scenario dealing with a real issue they would face if hired, and inviting your best finalists for a face-to-face interview with a committee.

Be Visible.

Show up. Your visibility on campus is directly linked to your success. Take an active part in opportunities outside of your department and get engaged on issues of University importance that may not be directly related to online learning. This strategy is especially important if you are a self-support unit that depends on departments to provide your courses and programs. Being visible will force you into a new reality of the larger culture and context in which your program belongs. Since that culture and contexts shifts, keeping your finger on the pulse is very important. You also need to tell your story and share your story. Do not assume that faculty, staff, and administrators know and understand the contributions that you make to the larger teaching and learning enterprise.

Be Flexible.

Be Flexible.

My version of flexibility is to have a lot of projects on the drawing board and to offer those ideas to our decision makers. The options allow us to move forward based on the interest of those in charge and prevents me from putting “my eggs in one basket” to use a colloquial term. Moreover, offering options for different ways that projects may evolve is an important strategy when presenting projects to your administrative leaders. Those making decisions want to consider different pathways and to see that you are open to pursuing multiple approaches towards the same end.

Avoid Being Disillusioned.

Accepting that “control is an illusion” (credit to Wayne Smutz at UCLA) will be the most empowering thing you can do for yourself. None of us are truly in control and remembering will help you to focus your energy on people and relationships. Building relationships and consensus on a path forward has produced the most challenging and rewarding times of my brief career. Accepting that I am not in control, but have influence has helped me avoid wasting energy on the wrong efforts. Remember to not take relationships you have successfully established for granted. I fell into this trap and realized that I had to do a better job of nurturing those original partners in my success. It is easy to get wrapped up in the day-to-day operations and forget how important strategic relationships are, especially when control is not reality.

Engage Faculty in Inclusive Problem Solving.

When we have a problem to solve related to Distance Learning at my institution, my staff and I do our very best to engage faculty. Be it testing an upgrade for our learning management system or discussing policies for student authentication, we ask faculty. Typically, we convene task forces or discussion groups. Set an agenda, moderate the discussion, and let our brightest resources (our faculty minds) problem solve with us. They appreciate being heard and contributing to a better path forward.

Find a Mentor.

I have had the good fortune of having seasoned higher education administrators and faculty members willing to serve as formal and informal mentors to me. Many times, I was being mentored without any awareness that mentoring was occurring. Without their guidance, I no doubt would have made more missteps than I am naturally inclined to make. The point is to find several people who you trust to be honest with you, seek their guidance, and apply what they advise. I am very grateful to those who have mentored me in the past five years of my current journey.

Be a Mentor.

In return for someone mentoring you, you should pay it forward by sharing what you have gained with others, especially your direct reports. The biggest impact you can have on your long-term organization’s growth is to invest your energy and time in those who work for you. I try to create work environment built on investing in my staff’s professional development, showcasing their talents, and pushing each beyond their individual comfort zones. The down side of my approach is the threat of poaching, but I prefer to see someone wanting to hire my staff as a compliment of how well they are being prepared for leadership. So, don’t be afraid to showcase your team’s talents and give them credit. You may end up reporting to them some day.

Timing and Being Told No.

If you want to have sustained success innovating, get used to being told “No!” Unfortunately, I had to learn not to take “No!” as a personal affront because of the time, energy, and effort I had put into a proposal. Over time, I began to understand that “no” really meant, more times than not, that the timing was bad. Asking at the right time or better yet, asking when would be a good time to  discuss X problem is the better solution. I am happy to report that I am experiencing more success when I ask the following. “When would be a good time for us to discuss ….?”

discuss X problem is the better solution. I am happy to report that I am experiencing more success when I ask the following. “When would be a good time for us to discuss ….?”

Not Finished.

I am not a finished product, nor is the unit I lead. I have to remind myself often of the strategies that got me here. And if there is one takeaway, it is to put people first. You can never go wrong by putting people first.

Learn More.

If you enjoyed this blog post, then I personally invite you to join me, Susan Aldridge, David Clinefelter, and Cali Morrison for “Developing and Sustaining Strategic Partnerships” at the WCET 2015 Annual Meeting on Thursday, November 12 from 9:45 – 10:45 am in Denver, CO. Come and join in an engaging meeting experience with leaders in many current and emerging aspects in the field of online learning.

Luke Dowden

Director of Distance Learning

University of Lousiana at Lafayette

Note about the author:

Dr. Luke Dowden is the founding Director of Distance Learning at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He was the inaugural recipient of the 2014 Online Learning Consortium’s Bruce N. Chaloux Award for Early Career Excellence in Online Education. He serves as the Chair of the WCET Steering Committee, a programmatic advisory group of leaders from WCET’s member institutions. Previously, he led the Louisiana Board of Regents adult learning initiative, Center for Adult Learning in Louisiana (CALL) and served as Dean of Accelerated Learning at Bossier Parish Community College.

Photo Credits:

There are really six parts to the book.

There are really six parts to the book.

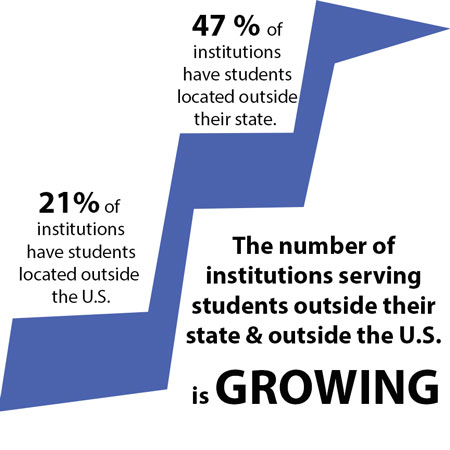

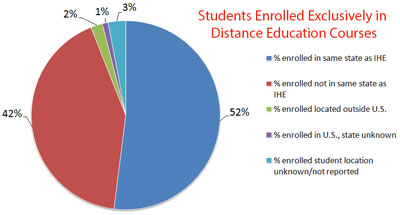

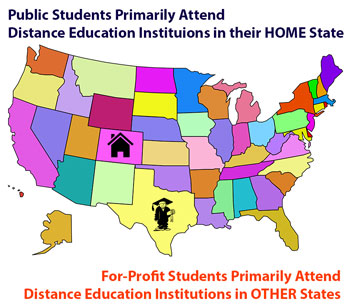

institutions reported 54% of their fully online students were in another state in 2012 and 56% in 2013, again this appears to be consistent data. There was growth in the reported number of fully online enrollments between 2012 (576,615) and 2013 (620,386). So while the proportion of enrollments reported as “not in the same state as the IHE” remained relatively constant (20% in 2012 and 21% in 2013) there were approximately 15,000 more out-of-state enrollments reported in 2013.

institutions reported 54% of their fully online students were in another state in 2012 and 56% in 2013, again this appears to be consistent data. There was growth in the reported number of fully online enrollments between 2012 (576,615) and 2013 (620,386). So while the proportion of enrollments reported as “not in the same state as the IHE” remained relatively constant (20% in 2012 and 21% in 2013) there were approximately 15,000 more out-of-state enrollments reported in 2013.