“You can please some of the people all of the time, you can please all of the people some of the time, but you can’t please all of the people all of the time”.” – John Lydgate

Abraham Lincoln referred to this quote after a difficult experience with another candidate. We are human. We don’t always agree with everything we are told or see. However, we do need to get the facts straight before we are vocal in our disagreement.

Recently, there has been some limited, but vocal opposition to the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement (SARA). The opposition has raised concerns specifically about abuse by for-profit institutions with a direct link to online education. One must be aware that abuse is not limited to the for-profit institutions and that many such problems occur at on-ground campuses not affected by SARA.

We condemn the bad actions of all institutions that employ predatory practices, misrepresent accreditation or authorization status, misrepresent job prospects and salary outcomes, and use high pressure sales tactics, whether for-profit or not.

Constructive discussion may be a cornerstone of American process, but allegations have been raised against SARA that requires fact checking. To that end, we would like to share issues critical of SARA and provide some objectivity and facts about each issue. Additionally, there are two documents that one should carefully review before making a determination of the feasibility or reliability of SARA. These documents are: the Unified SARA Agreement and the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement Policies and Standards. Both will be included in the new SARA Manual due out in June, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWrG6l-5CAg

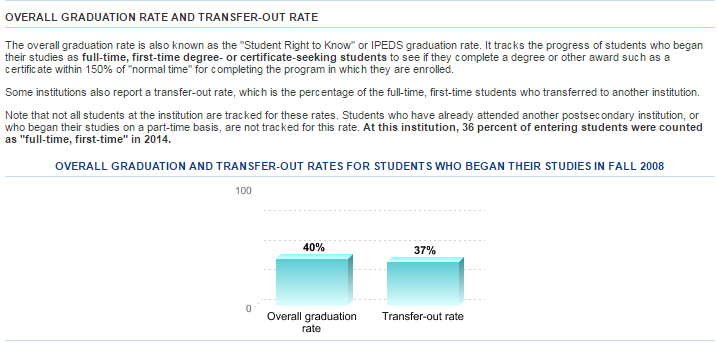

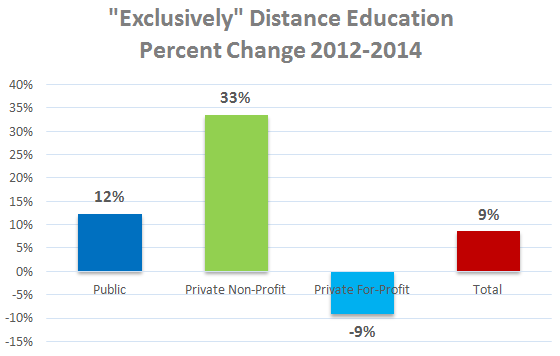

Myth #1: For-profit institutions offer almost all distance education. For-profit and online education is conflated.

Facts: According to the U.S. Department of Education’s IPEDS Fall Enrollment data for Fall 2014:

- For-profit institutions enrolled only 30% of students who took all of their classes at a distance.

- For-profit institutions enrolled only 17% of students who enrolled in at least one distance education course.

The closure of Corinthian Colleges last year was one of the most publicized and largest shutterings of a for-profit college in recent years. Operating under several names, Corinthian Colleges was a “career college” with the bulk of its students learning in a face-to-face setting.

For SARA, only about six percent of institutions participating in it are for-profit. Most of them are public.

Opinion: In a letter to the New York State Education Commissioner, there is repeated reference to “predatory online companies,” which is an apparent attempt to demonize all distance education providers. While there have been predatory online institutions, this reference is being applied very broadly.

There is often the suggestion that online education is synonymous with fraud. As shown with the Corinthian College case, misrepresentation and fraud can happen anywhere.

While trying to attack the for-profit colleges by assailing SARA, there is little worry about the collateral damage to students attending public and non-profit institutions.

Myth #2: States already provide superior oversight of out-of-state institutions offering online courses to students in their state.

Facts: Most states do not regulate institutions who only offer 100% online courses to students in their state. SARA makes no such distinction, as it prompts review of an institution for initial SARA admission and review for annual SARA renewal. Additionally, SARA provides the student the ability to file a complaint in the institution’s home state, which has the most knowledge and understanding of the institution. Therefore, students who were previously not protected (because their state did not regulate an institution that served students only by online means) are now protected by SARA provisions.

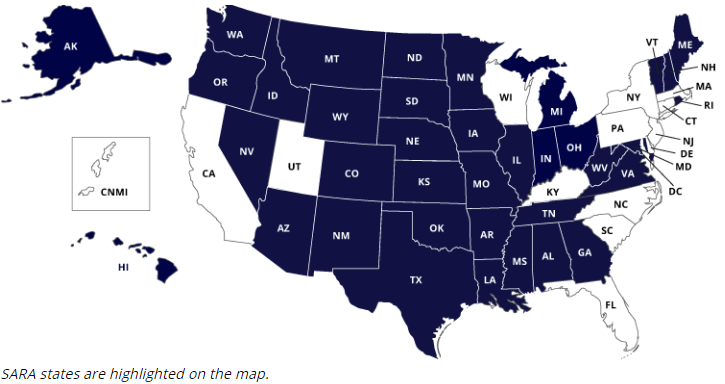

Opinion: Many of the states (MA, CA, NY, and WI) in which there has been opposition to SARA do not regulate 100% distance education activities offered by out-of-state institutions. If the complaint is that SARA provides insufficient oversight, why aren’t these states regulating distance education of all out-of-state institutions? SARA represents improved student protection in those states.

Myth #3: SARA was developed solely by the colleges without any consumer protection advocates.

Facts: SARA was developed openly in three phases:

- In 2010, Lumina Foundation funded the Presidents’ Forum and the Council of State Governments to develop a Model reciprocity agreement allowing states to acknowledge other states’ decisions in regard to institutional authorization. The Drafting Team included three state regulators, a former state regulator, a State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO) officer with regulator duties, two regional higher education compact representatives, two institutional representatives, and a state legislator. Consumer protection was at the center of these discussions. Listening sessions were held with regulators, accreditors, and the higher education presidential groups. Drafts of the model agreement were widely circulated for public comment.

- In 2012, building upon the work of the Presidents’ Forum and Council of State Governments, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) advanced the next version of an agreement in collaboration with the other regional higher education compacts (Midwestern Higher Education Compact, New England Board of Higher Education, and Southern Regional Education Board). Drafts of proposed agreements were openly shared for public comment.

- In 2013, the Commission on the Regulation of Postsecondary Distance Education (chaired by former Secretary of Education Richard W. Riley) was created by SHEEO and the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities. Many SHEEO offices include state regulators. After publishing a draft for open comment, in April 2013 the Commission issued its final report recommending SARA’s structure.

Opinion: State regulators were involved throughout the processes. These regulators are the members of the consumer protection community most familiar with laws, regulations, and infractions surrounding state authorization oversight. In each phase, draft documents were openly shared and public comment was sought. The SARA development process started in 2010. While a few state regulators have opposed the idea of SARA all along the way, organized opposition is recent. There are now 37 SARA states and soon to be at least 40. (See www.nc-sara.org) Why are objections arising so late in the process? And why has SARA been so successful if it is so dismissive of students’ rights?

Myth #4: SARA should regulate the bad guys more than the good guys.

Fact: SARA’s requirements apply to all institutions equally.

Opinion: The good guys have nothing to worry about.

In a letter denouncing SARA, former Senator Tom Harkin (IA) opines: “For reasons that fly in the face of the philanthropic mission of the public and nonprofit institutions, the model act they helped draft actually forbids states from regulating differently based on sector. That’s right. Under SARA, Massachusetts is forced to regulate Harvard the same as it regulates ITT. If it doesn’t, then Massachusetts is kicked out of SARA and Harvard has to get approval from each state to offer online education. This is simply not the way it should work.”

That sounds logical until you realize that it is not just the for-profits that break the laws. Yes, there are for-profits that have committed heinous acts of misrepresentation and abuse. They should be punished.

In our work in the State Authorization Network, we have heard from large institutions with familiar names that are openly flouting state authorization laws. We have followed major state universities that have deceived and failed students by enrolling them in academic programs in licensure fields when the student could not practice in their state of residence. Small non-profit institutions can close the same way for-profits can—Burlington College did so last week.

Are transgressions by public and non-profit institutions less common? Probably. But how do you know who is going to become a bank robber until they rob a bank? The regulations should apply equally to all.

Myth #5: The institution’s home state is the only state involved in the resolution of a student’s complaint.

Fact: The SARA Policies and Standards Section 4 Subsection 2 provides the complaint process for SARA institutions. The process is more thorough than the myth indicates. A student may appeal the decision arising from an institution’s own complaint resolution procedure to the SARA portal agency (the agency handling SARA matters) in the home state of the institution. The agency will then notify the portal agency for the state in which the student is located. The resolution of the complaint will be through the complaint resolution process of the institution’s home state, but the states will work together to identify bad actors. Additionally, complaints are reported and reviewed by the regional compact to provide oversight of the state to ensure the state is abiding by SARA standards. This streamlines the line of complaint resolution and keeps the resolution within the laws of the state under which the institution applied to participate in SARA.

Additionally, this process allows NC-SARA to track any emerging patterns in student complaints and take swift investigative action if necessary. This is important as attorney generals in the states may be slower to act due to too few bad actors and little evidence of bad actions. SARA publishes quarterly on its website a list of complaints against colleges that have been appealed to the SARA portal agencies, while most states do not

Opinion: There is strength in states working together to identify and resolve student complaints and correct offending institutions.

Myth #6: Student complaints can be resolved only by the laws and agencies of the institution’s home state.

Fact: The SARA Policies and Standards Section 4 subsection 2 g. provides that there is nothing in the SARA Policies and Standards that precludes the state attorney general from pursuing misbehaving institutions that break state consumer protection laws. Additionally, a violation of a federal regulation (such as that which rises to the level of a federal misrepresentation action) is still under the jurisdiction of federal authorities to pursue any actions against the institution.

Myth #7: SARA requires student complaints be resolved by the institution. This is the same method that for-profit colleges use to hide complaints.

Fact: SARA follows a practice commonly used by states throughout the country that encourage students to exhaust local options before appealing to the next level. There is no requirement that the complaint remain at the institution. If an institution is stalling or not dealing with the student’s complaint and the institutional complaint process is not yet complete, that student still has the option to appeal to the appropriate SARA portal agency.

According to Section 4 (Consumer Protection) subsection 1 of the SARA Policies and Standards document: “Initial responsibility for the investigation and resolution of complaints resides with the institution against which the complaint is made. Further consideration and resolution, if necessary, is the responsibility of the SARA portal agency, and other responsible agencies of the institution’s home state (see the following section: Complaint Resolution Processes).” The student is expected to begin with the institution, but that is not the end of the student’s options.

Opinion: Again, the critics are confusing this provision with the actions of several for-profit institutions, which require students to sign mandatory arbitration agreements that foreclose their external routes to seek redress. Under pressure from the Department of Education and others, two for-profit universities recently decided to remove arbitration requirements from their enrollment agreements. Even if the for-profit institution requires mandatory arbitration, to remain a SARA member, the institution has to allow the student to use the SARA complaint process.

Myth #8: The purpose of SARA is to make it easier for the institution.

Fact: According to the Operational Principles of SARA, found in Section 2 of the Unified Agreement: “…the purposes of this Agreement are to:

- Address key issues associated with appropriate government oversight, consumer protection, and educational quality of distance education offered by U.S. institutions.

- Address the costs and inefficiencies faced by postsecondary institutions in complying with multiple (and often inconsistent) state laws and regulations as they seek to provide high-quality educational opportunities to students in multiple state jurisdictions.”

Opinion: Many institutional personnel also think that SARA is merely to make life easier for them. The primary purposes are listed in the first bullet. Without performing the regulatory requirements outlined in the first bullet, then any institutional benefits are not worth it.

Myth #9: SARA won’t provide enough oversight to protect students from the bad practices of an institution like Trump University.

Fact: Trump University was a non-accredited and non-degree conferring institution that would never have been eligible to become a SARA institution. Per Section 3.2 of the Unified Agreement, an institution must have the following characteristics to be eligible to participate in SARA:

- Location: The institution is located in the United States, its territories, districts or Indian reservations.

- Identity: The institution is a college, university or other postsecondary institution (or collection thereof) that operates as a single entity and which has an institutional identification (OPEID) from the U.S. Department of Education. This includes public, non-profit private and for-profit institutions.

- Degree-granting: The institution is authorized to offer postsecondary degrees at the associate level or above.

- Accredited: The institution is accredited as a single entity by an accreditation agency that is federally recognized and which has a formal recognition to accredit distance-education programs.

Myth #10: Institutions will shop for the lowest-regulated state or use back door acquisitions.

Facts: According to the Roles and Responsibilities of Participating States, found in Section 5 of the Unified Agreement, each state joining SARA must agree that this agreement has the capacity to perform several tasks, including:

- “It has adequate processes and capacity to act on formal complaints…”

- Demonstrate that consumers have adequate access to complaint processes.

- Ability to document complaints received, actions taken, and resolution outcomes.

- Notify institutions and (if appropriate) accrediting agencies of complaints filed.

- “It has processes for conveying to designated SARA entities in other states any information regarding complaints against institutions operating within the state under the terms of this agreement, but which are domiciled in another SARA state.”

- “It has clear and well-documented policies for addressing catastrophic events.”

Opinion: The purpose of SARA is to establish a common baseline for regulation of interstate activity. It does the institution no good to shop for the lowest-regulated state, as the bar is set at the same height in all states. If a state is somehow shirking its duties, SARA gives other states leverage to pressure them to meet their responsibilities.

Myth #11: SARA will require institutions to accept transfer from other colleges.

Facts: Transfer is not a part of this reciprocity agreement. As stated in the opening paragraph of the SARA Policies and Standards, SARA is an agreement “that establishes comparable national standards for interstate offering of postsecondary distance-education courses and programs.” The focus is on the activities offered in other states to students of the institution.

Myth #12: There is a better reciprocity option through the “Interstate Distance Education Reciprocity Agreement” between Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Fact: Although a reciprocity model was offered by a critic of SARA in a recent letter to the New York State Commissioner of Education, this model does not appear to exist. Research of legislation in each of these states, review of each state’s higher education websites, review of the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO) Surveys maintained by each state’s higher education agency, consultation with institutions in each state and a direct request to the Connecticut Office of Higher Education lead us to the same conclusion. There is no Interstate Distance Education Reciprocity Agreement between Connecticut and Massachusetts.

There have been papers published by SARA critics suggesting what a “good” reciprocity agreement might include. They always end with allowing each state to essentially take any actions it wishes to take regarding an out-of-state institution. That’s not reciprocity. That’s the current state of affairs that so poorly serves students and institutions alike.

Meanwhile, Connecticut’s legislature has just passed legislation allowing it to join SARA.

In Conclusion…

The sharing of critical analysis of the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement is healthy to provide states, institutions, lawmakers, and citizens the ability to assess the pros and cons of this new process. However, to publicly report an analysis that fails to show completed research or understanding of the language of the Agreement is a disservice to the states, institutions, lawmakers, and citizens. Please review the Unified SARA Agreement and the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement Policies and Standards before making any judgments about the viability of SARA. We hope that the presentation of the publicly reported “myths” and corresponding facts will aid your ability to make an appropriate judgment.

In Disclosure…

In this era of ad hominem attacks we have focused on the statements that we feel are erroneous or misleading and not the personalities involved. In case you wonder why we care about these issues, here is a brief background about the two of us:

- Russ Poulin served on the original drafting committee and the WICHE committee that developed the language that became SARA. Every discussion in those meetings took the student protection responsibilities very seriously. I developed the WCET State Authorization Network to help institutional personnel navigate and comply with each state’s regulation.

- Cheryl Dowd is a former institutional compliance officer who now directs the WCET State Authorization Network, which serves more than 75 members encompassing more than 700 colleges and universities.

While others in higher education circles have merely railed against any type of regulation, we have been consistent in trying to find a balance that meets the needs of parties, regulators, institutions, and consumers.

Russell Poulin

Russell Poulin

Director, Policy & Analysis

WCET – WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies

rpoulin@wiche.edu

wcet.wiche.edu

Twitter: RussPoulin

Cheryl Dowd

Cheryl Dowd

Director, WCET State Authorization Network

WCET – WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies

cdowd@wiche.edu