Instructional design has a problem. I noticed it last summer when I was doing the conference circuit. We have run out of things to say. Keynotes, which are supposed to rally the troops and get us fired up for the day, offer only platitudes. Sessions are dull, lifeless. Birds of a Feather sessions never take flight.

Instructional design has stagnated.

How Did We Get Here?

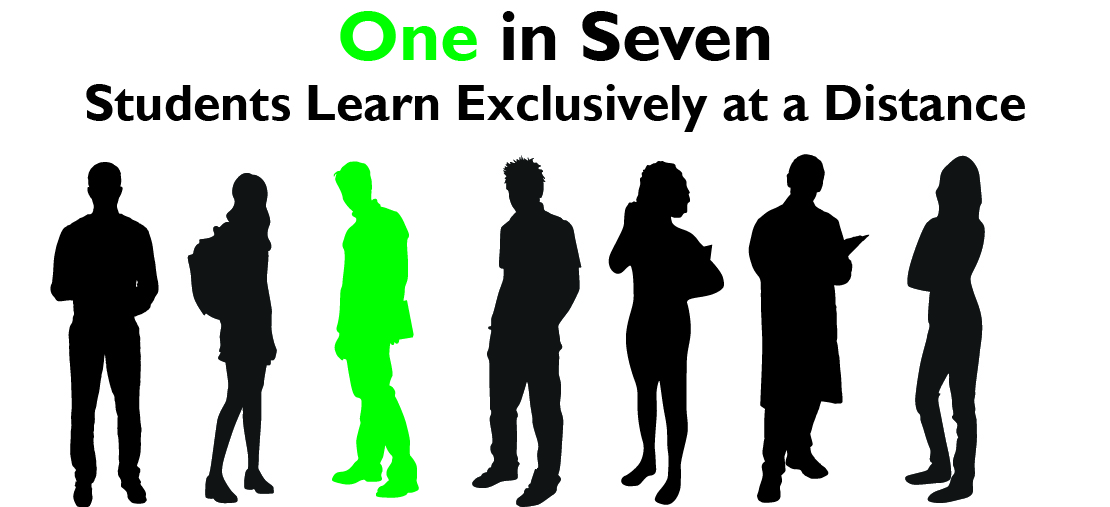

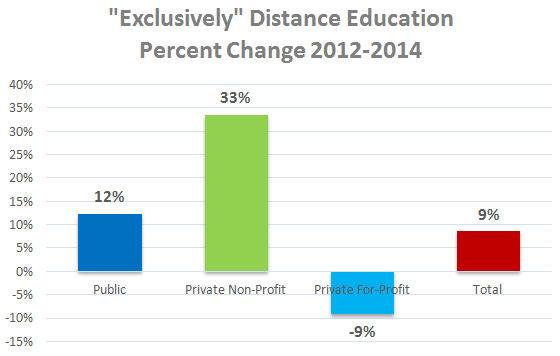

It took me a while to understand why. After all, we are living through the middle of an upheaval in online and hybrid education in higher ed. After years of second-class status, online courses have finally become part of most college students’ experience for at least one class. Even traditional, face-to-face courses use online content regularly. We made it, or at least we are making it.

Obviously there is good work happening in instructional design. We are working in the most innovative sector of higher education today. Yet the problems we each face in our own ID shops across the country point to the underlying problems facing the field. First, many faculty still do not trust online education. Second, students tend to choose online classes because of their schedules, not because these are “great classes.”

I think these two problems are related, and I think instructional design is causing them.

Instructional Design Starts with “No”

Today’s instructional design models are hamstrung because they make the mistake of starting with “no.” To the faculty we say “no, you can’t run the class the way you always have.” “No, your objectives aren’t measurable.” “No, you can’t change things on the fly.” And we say these things for good reason.

Online and hybrid classes feel like special cases. The delivery is different, so the courses must be different too. Measurable objectives can be very important because they are tied to accreditation and funding. Having a course fully built before students arrive can be critically important, especially if there is a question about whether they will ever get finished at all.

But when we walk in to a faculty member’s office and start with “no,” we lose too much. We lose the opportunity to learn who that person is as a teacher. When we focus on our list of “no’s,” we don’t give them an opportunity to show us what they are good at and how we can translate that skill and passion to a new medium.

I’ve been working in instructional design a long time. I know the biases that many designers have. I’ve heard more than one of my peers posit that even face-to-face classes would be better if we could get our hands on them. If faculty sometimes feel insulted by a designer’s suggestions, they probably have a good reason. A healthy sub-group of designers assume that most faculty are not good teachers, and are not interested in teaching well or improving.

Think about that. If I started this blog with “you probably don’t want to be a better instructional designer” would you listen to anything I have to say? Not likely. Whether you want to improve or not, I’m not going to get your attention and buy-in if I assume that you don’t.

And doesn’t that make sense? When we start with “no,” we never learn the best our faculty have to offer. When we design around “no” we get what we ask for. We get something less. Then we give that lesser product to the students. Is there any wonder why students don’t choose online classes because of their inherent worth?

How Do We Fix This? Green Light Design

How Do We Fix This? Green Light Design

I propose a change in attitude. My coworker, John Jones, and I have worked together to begin designing a new model for instructional design we are calling “Green Light Design.” We propose turning today’s red lights to green. We propose starting with “yes” and not “no.”

We have been using the Green Light philosophy at Wichita State for over a year now, and it seems to be working. When we start an instructional design project, we never begin with talk of rubrics, measurable outcomes, or specific tools. All of those conversations lead to early no’s. Instead, we sit down and ask “what do you love about teaching?” “What do you want your students to learn?” “Tell me, if I could give you everything you are wishing for, what would that look like?”

We start with “yes.”

By starting out this way, we make our faculty the experts, and we communicate that we respect what they do. In turn, they quickly come to respect our design experience, our technical expertise, and our willingness to listen. We give them our attention, and they give us theirs. And the courses we design together are better for it.

If you would like to try to adopt a Green Light philosophy, let me suggest you think through our LEARN model. LEARN got its name because the word “learn” has gotten such a bad rap as not being measurable. Believe me, an outcome or objective that uses the verb “learn” is not going to make it through many rubric processes. But I like the idea that it’s our job to help people learn, so we used it to remind us how we like to design courses:

- Listen: Always start any instructional design project by listening to your faculty.

- Envision: Blue sky your design. Don’t limit yourself to what your tools can do, to what your rubrics insist upon, or to what you have done before.

- Adjust: Choose what you can do now, and start there.

- Revise: Working with your faculty member, fine-tune what you have, add what you can, and do the hard job of getting things working.

- Negotiate: Good design is a long-term project, and both you and the faculty member are on the same team. What do they want next? What can you do? Don’t assume that you know what should come next, but don’t assume your faculty member necessarily knows that either. Both of you need to be in on making the course better over time.

Starting with “yes” has been working for us. Our boutique designs are leading to excellent courses, and people are getting happier. It’s possible to get measurable outcomes and well-organized courses this way, I promise. And along the way, I think you’ll find that if you start with yes, you and your faculty are going to have much more fun.

Carolyn Speer Schmidt

Manager, Instructional Design and Technology

Wichita State University

carolyn.schmidt@wichita.edu

Photo credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Traffic_signal_signs

Some other lessons that we have learned:

Some other lessons that we have learned:

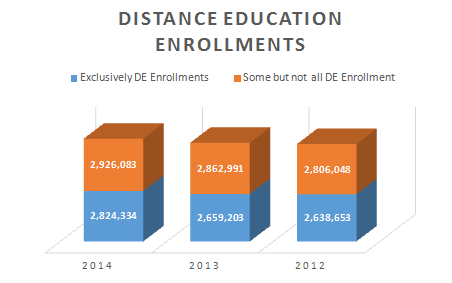

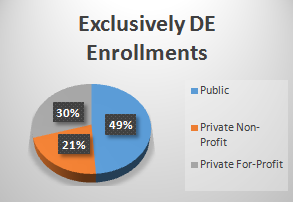

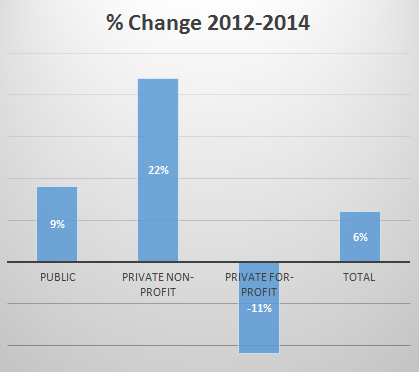

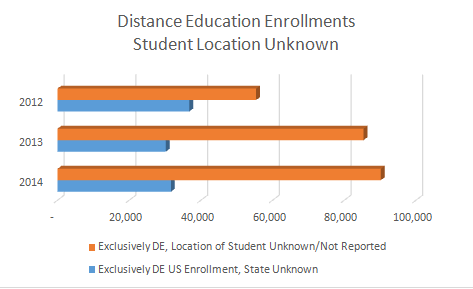

Highlights of Enrollment Analyses

Highlights of Enrollment Analyses

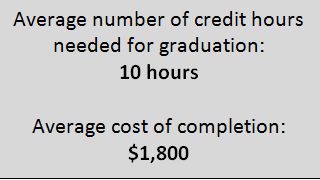

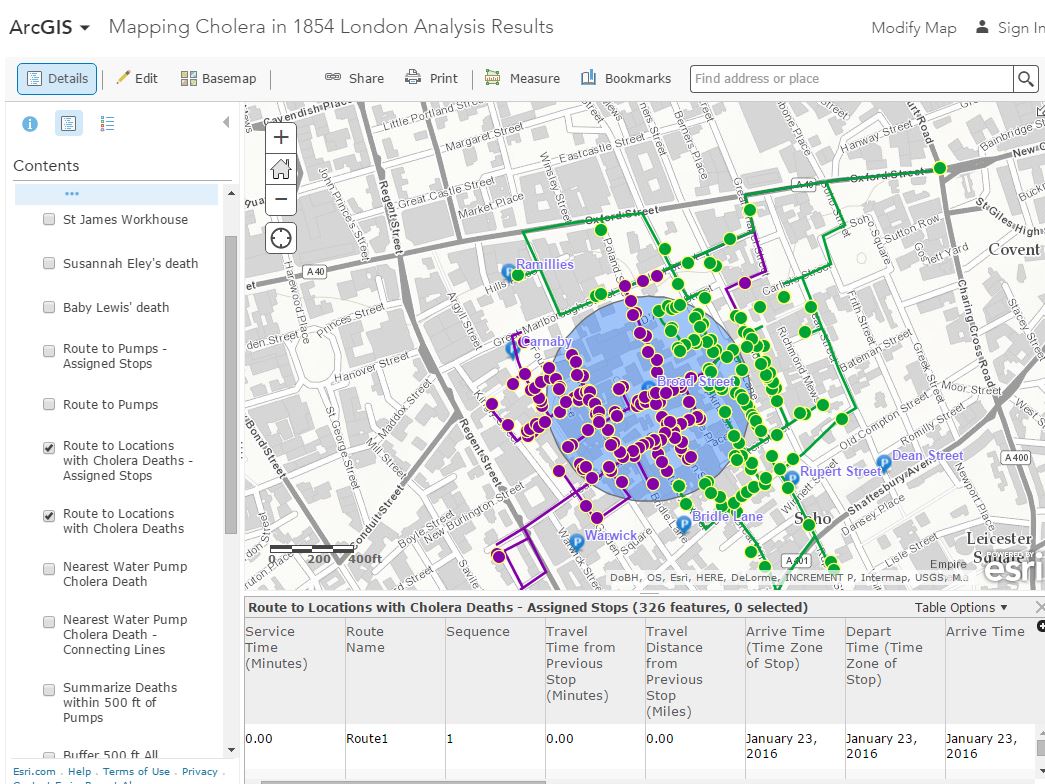

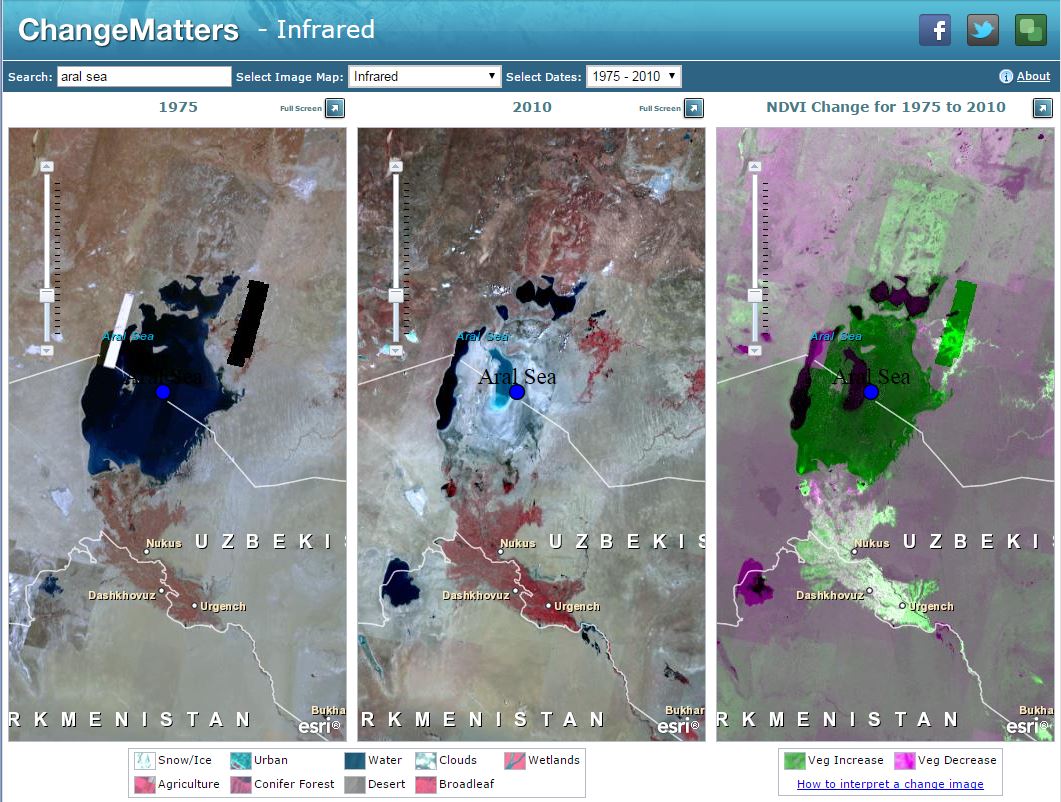

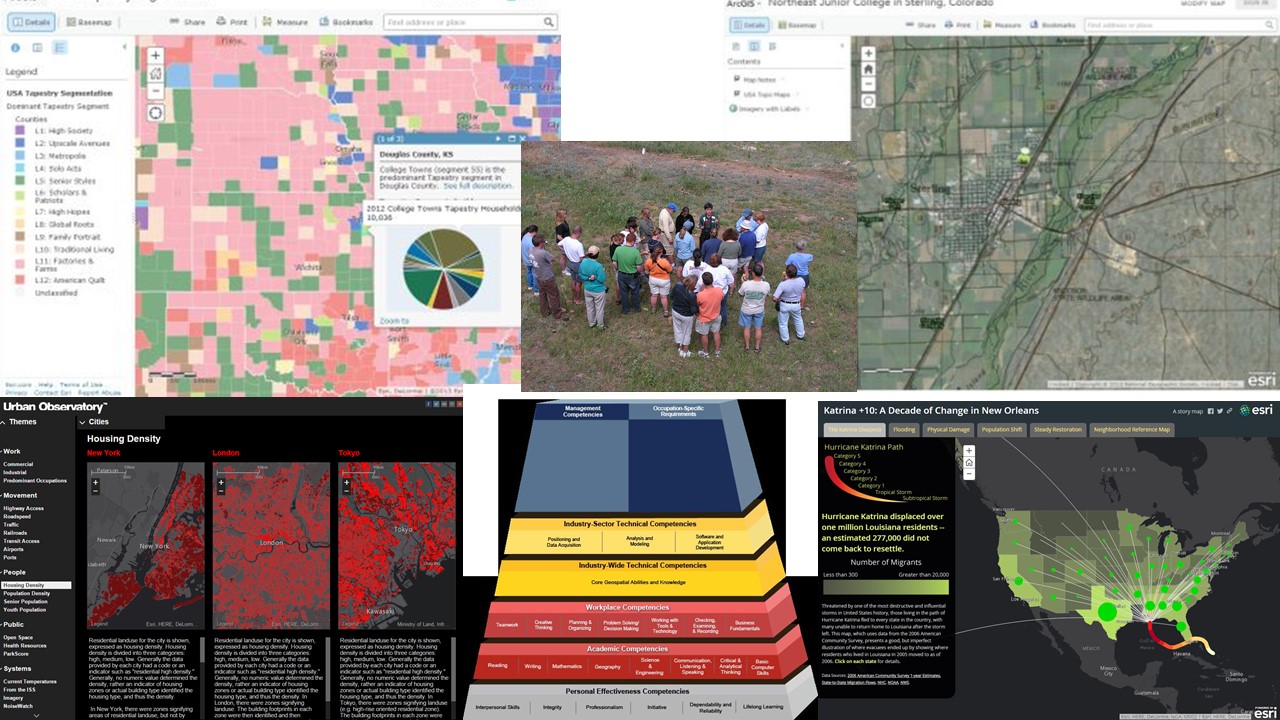

On one side of the handout is a series of infographics highlighting the differences in higher education from 1965 to today. We provide several statistics that show the changed nature of both the learner and the use of educational technologies in shaping the learning experience. It’s important to look beyond online learning to how educational technology is having an impact on teaching in any venue.

On one side of the handout is a series of infographics highlighting the differences in higher education from 1965 to today. We provide several statistics that show the changed nature of both the learner and the use of educational technologies in shaping the learning experience. It’s important to look beyond online learning to how educational technology is having an impact on teaching in any venue.