Have you met Robbie Melton, Tennessee’s emerging education technologies evangelist? We sent her back to the future and an in today’s guest blog post, she shares what she found there. Thank you Robbie!

What are your thoughts about the future?

Russ Poulin, WCET

Hello, I’m Robbie Melton, and I’m writing this blog from the future, the Year 2050. Come join me in a futurist discussion of how technology has transformed education in the years to come.

Hello, I’m Robbie Melton, and I’m writing this blog from the future, the Year 2050. Come join me in a futurist discussion of how technology has transformed education in the years to come.

Blogging to you from 2050, I want to reveal that everything that I interact with including utensils, clothing, furniture, flooring, lights, cars, weather, people, and even myself will instantaneously and automatically provide data ‘to me’ and ‘about me’ that will determine on-demand in real time my education pathways. I want you to know that in the future that I am my own teacher, evaluator, and employer.

The predictions by Tina Barseghian, ‘School Day of the Future in the Year 2025’, are now universal standards across the globe , “Gone are the days when the adults involved in learning primarily served as teachers, administrators, and tutors. Now a whole host of learning agents support learning, with some specializing in particular content and others focusing on pedagogy or assessment design. Networked collaboration is the norm.” Furthermore,

- Amid a culture of flexible innovation, learners shape their own learning experiences, drawing upon a rich learning geography to identify resources that meet their needs.

- Personalization of learning experiences are the norm, so the K-20 system no longer dominates learning. Those schools and districts that remain have become part of a complex and vibrant set of options that together form a loose learning ecosystem. Learning is available 24/7 and year round across many learning platforms and beyond geographic limits.

- Smart networks of resource providers form lightweight, modular learning grids to offer flexible learning experiences as demand dictates.

Would you believe in the future that there is no more teaching; only learning; no more schools and classrooms, only 24/7 living learning environments; and no more curriculums, only data driven content for addressing learning on-demand and/or prepared predictive based learning. Yes, Hal Varian’s vision, Chief Economist for Google, is now a reality, “The biggest impact on the world is the universal access to all human knowledge.” There is no limitation to Internet access and mobile devices, smart tools and wearable data tech are available at no cost to everyone worldwide. Please know that this is having a significant impact on literacy and numeracy; resulting in a more informed and more educated world population.

Come take a peak of my world in 2050. Watch how we are incorporating education and technology into our daily lives:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BDiqP8mInx8&w=560&h=315]

You will note that the primarily role of an educator in 2050 is to design and code/program items and situations (virtual, augmented, and real) for students to interact with and to connect to for personal and adapted learning opportunities.

Also, in 2050, the core design of education delivery is based on “A global, immersive, invisible, ambient networked computing environment built through the continued proliferation of smart sensors, cameras, software, databases, and massive data centers in a world-spanning information fabric known as the Internet of Things” . Many of the following innovations were predicted by the Pew Research Center’s Internet Project way back in 2014,

- Information sharing over the Internet will be so effortlessly interwoven into daily life that it will become invisible, flowing like electricity, often through machine intermediaries. The spread of the Internet will enhance global connectivity that fosters more planetary relationships and less ignorance.

- The Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and big data will make people more aware of their world and their own behavior.

- Augmented reality and wearable devices will be implemented to monitor and give quick feedback on daily life, especially tied to personal health.

For degree obtainment and verification, David Hopkins’ (2014) forecast is now mainstreamed, “Competency-based degrees are no longer limited to schools, colleges, or universities in providing the learning ‘degree’. Students are now able to take MOOCs from anyone and any provider, whereas, businesses like Starbucks can now provide their staff with ‘degrees’ depending on the prescribed content and outcomes. . . .Unlike in the past, the best tutors will not be professors or dons, but something similar to coaches and caddies, there to help motivate, soothe after frustrations, and offer advice on which tools to use in a rough spot. . .

Unfortunately, in the Year of 2016, we are still addressing ‘human dynamics and social issues in education’, “even in 2050, computers will not have cured us of vanity and folly. Although it may be faster, cheaper, and easier to learn anything than ever before, the status-based campus may be with us yet.” – See more of this look at the future by David Hopkins.

Click here to transport into the Year 2050 Blog.

Together, we will address questions and concerns about the future impact of the transformation of education and technology based on leading futurist experts and your insight). Let’s explore the possibilities for shaping education for the 22nd Century….or next semester, whichever comes first.

Dr. Robbie K. Melton, 2016

1St App-ologist (Curator of Smart Apps and EduGadgets as Education and Workforce Tools)

Associate Vice Chancellor for Emerging Mobile Technologies

Tennessee Board of Regents

www.appapedia.org

References:

Tina Barseghian, ‘School Day of the Future in the Year 2025’, are now universal standards across the globe

http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/2011/01/12/school-day-of-the-future-learning-in-2025/

Hal Varian’s vision, Chief Economist for Google, Digial Digial Digital Life in 2025 BY JANNA ANDERSON AND LEE RAINIE

http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/03/11/digital-life-in-2025/

The World on 2050 the Best Technology Best Education (YouTube: https://youtu.be/BDiqP8mInx8)

David Hopkins, Classrooms in 2050, Technology Enhaned Learning Blog,

http://www.dontwasteyourtime.co.uk/elearning/classrooms-in-2050/

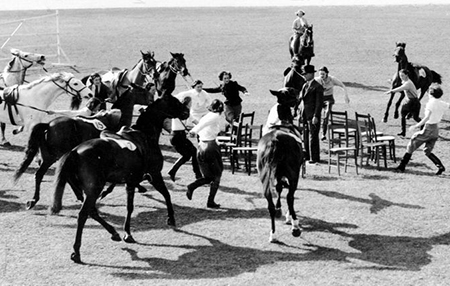

This fracturing will occur within the context of worsening budget woes for most institutions, be they public, private, or proprietary. As admissions flatten and/or decline, state appropriations flatten and/or decline, and the federal government ratchets up its accreditation, accountability and loan reforms, many existing institutions find themselves in a large-scale version of musical chairs, trying desperately avoid being among those without a place to sit when the music stops.

This fracturing will occur within the context of worsening budget woes for most institutions, be they public, private, or proprietary. As admissions flatten and/or decline, state appropriations flatten and/or decline, and the federal government ratchets up its accreditation, accountability and loan reforms, many existing institutions find themselves in a large-scale version of musical chairs, trying desperately avoid being among those without a place to sit when the music stops. Peter Smith

Peter Smith

I had the opportunity to participate in this session with Dale Johnson, Arizona State University, as well as Thomas Cavanagh, University of Central Florida, Dror Ben Naim, Smart Sparrow, Nick White, Capella University, and Judith Komar, Colorado Technical University, arguably a panel of the top leaders in adaptive learning. The session was

I had the opportunity to participate in this session with Dale Johnson, Arizona State University, as well as Thomas Cavanagh, University of Central Florida, Dror Ben Naim, Smart Sparrow, Nick White, Capella University, and Judith Komar, Colorado Technical University, arguably a panel of the top leaders in adaptive learning. The session was  The non-profit

The non-profit

o them. The Southern Regional Education Board has developed

o them. The Southern Regional Education Board has developed  In addition to the concrete examples presented, more general considerations—for example how new types of credentials such as digital badges might fit into a

In addition to the concrete examples presented, more general considerations—for example how new types of credentials such as digital badges might fit into a  Christina Sedney

Christina Sedney