Overview and Introduction

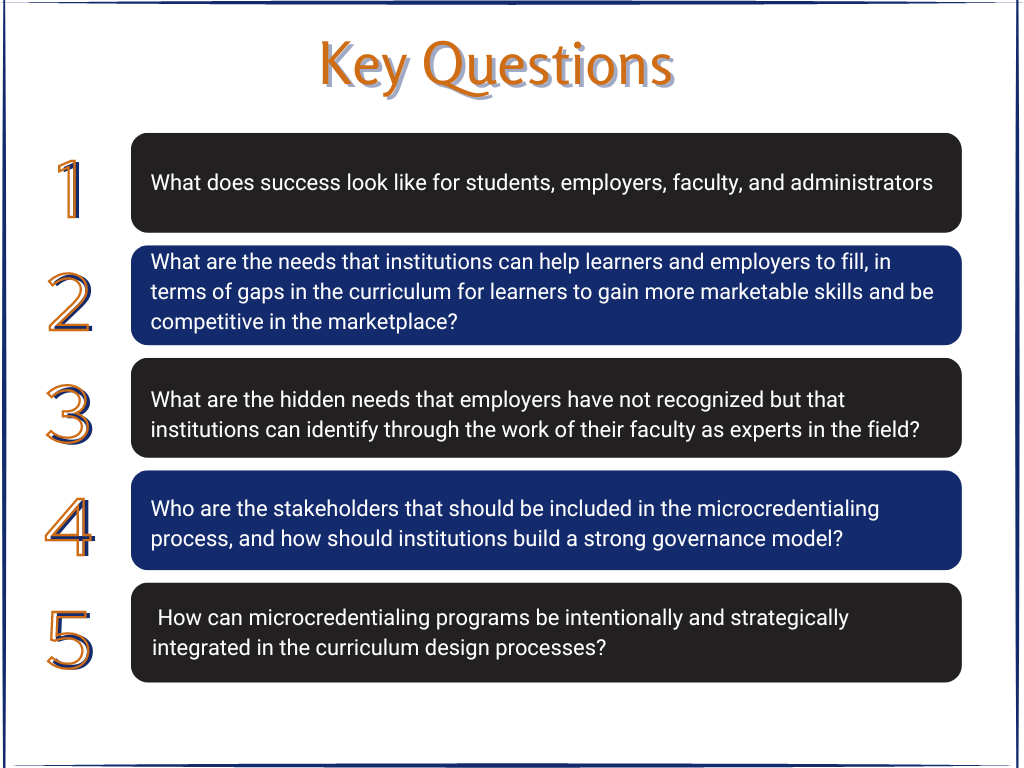

Today, we conclude the WCET blog series on microcredentials which set out to address the inception, implementation, and evaluation of microcredentialing approaches across the higher education industry. We learned that there is a wide range of reasons for an institution to begin a microcredential initiative, an even broader spectrum of microcredential terminology, and yet two primary outcomes: “to improve student recruitment and retention” and “to align learning with shorter-term outcomes that can more immediately align with career progression” (Niles and Lazarewicz, 2022). Institutions and training providers use microcredentials to adapt to a number of trends such as decreasing student enrollment and workforce degree requirements and increasing acceptance of online learning, employer demand for skills training, and public demand for greater return on educational investment (Higher Learning Commission, 2022). As professionally trained and former instructional designers, we begin by defining what success looks like. In this blog post, we will present what we learned about how to assess and evaluate the efficacy of microcredentialing approaches through a variety of stakeholder perspectives.

Multiple Perspectives on Success

“One of the positives from the pandemic has been the acceleration of innovation and change in higher education – microcredentials have grown in scale and areas of focus to help provide current students or adult learners additional knowledge to help them be more competitive in the job market. The assessment and evaluation of whether these microcredentials are making a difference for students and adult learners and whether employers value these micro credentials. The next phase of the growing area of microcredentials should seek to answer the questions about employer value, industry microcredentials, or higher ed developed micro credentials, measuring learning outcomes, and more,” shared Melissa Vito, Vice Provost of Academic Innovation at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Microcredentials should create positive labor market outcomes in terms of employment and earnings. “If done correctly, microcredentials help students develop skills that today’s employers are expecting from their entry-level talent” stated Scott Shireman, Global Head of Coursera for Campus. “When microcredentials are built and recognized by industry leaders like Google, IBM, and Meta, they reflect the skills and tools most in-demand by top employers.” Shireman also invited us to consider how microcredentials impact students. “From a student recruitment perspective, the fact is that students today, and their parents for that matter, are thinking more critically about the ROI of the traditional four-year degree. We’re seeing that shift in mindset reflected in university recruitment numbers. It’s a very competitive landscape, and universities are increasingly leveraging microcredentials and job-relevant skills training to differentiate their brand and show students that they’ll benefit from multiple signals in a competitive and fast-evolving market – the two or four-year degree they graduate with, and the career certificates they earn along the way.” The new Coursera survey published shows high demand for industry microcredentials from students and employers in tight labor market.

Kate Smith, President of Rio Salado College, reinforced that student success is at the core of an effective microcredential: “Evaluation of microcredentials is tied to outcomes of students – retention, completion, post-completion employment, and wages, along with structured qualitative feedback from learners, employers, and related faculty and staff.” Microcredentials can provide students with early exposure to career choices, helping students to “build confidence to continue their post-secondary education” and also to reinforce or redirect career choices.

For former Mesa Community College student, Sam McFadden, a two-week, full-time “wire harness bootcamp quite literally changed my life, and has put me in a position to be successful in my career, and complete my education. Three years ago, it would have been difficult to imagine that I would be where I am today.” Today, Sam is employed by Boeing, the world’s largest aerospace company.

Jude Chudi Okpala, Professor of Instruction at the Department of Philosophy and Classics at The University of Texas at San Antonio explained what success should look like for students. “Success in a critical thinking microcredential, for example, consists in application of critical thinking on a concrete and real problem. Looking at students’ work in such microcredentials, one sees a correspondence between the objectives and the learning outcomes for the microcredential: for example, evidence of logic in addition to effective understanding of complexity and the relationship between the problem and solution. Invariably, a successful microcredential in critical thinking should reveal independent thinking and the students’ ability to solve a concrete problem. The microcredential should demonstrate without ambiguity the students’ skill in critical thinking/problem-solving.”

Lisa Larson, President of Eastern Maine Community College, Ed Design Lab, Designer in Residence believes “micropathways are the gateway to transformation” because this demonstrates “we are committed to transforming our institution to meet the needs of those who need us most.” Larson emphasized the need to measure the engagement, student and employer value proposition, and impact after completion. For example, getting employers to include microcredentials in their recruitment, hiring, and promotion practices are metrics of success. In short, Larson asks “Who did the microcredential make a difference for, and how can we tell the story of impact?” Microcredentials may also increase access for non-traditional students to “break through ceilings” and “earn a living wage” contributing to equity and economic growth in our communities. Larson advised that microcredentials should be “digitally discoverable”, so students can “own the learning upon receiving validation of the competency and skill.” The digital nature of a microcredential should “create the visibility for students to take every ounce of learning and experience with them.”

Assessment and Evaluation

“Ideally a feasibility study includes a market review of demand, wages, stakeholders, and resources needed to build and implement the credential, combined with a SWOT analysis. The microcredentials are then developed with input and co-design principles when feasible, with local or national industry partners” (Kate Smith, 2022, personal communication). Data analysis plays a key role in evaluating the effectiveness and impact of scope, resources, risks and feasibility of a microcredential project. Consensus-building with campus stakeholders and employer stakeholders is critical to a mutual definition of what success looks like.

Lydia Riley, Chief of Staff of The University of Texas System (UT System) invites institutions to consider the “AGILE planning framework with frequent feedback loops that lay out the foundations of the microcredential programs, identifying strategic goals for revenue-generation or mission-enhancing endeavors”. All stakeholders expressed a desire for marketable skills, relevant, contextualized curriculum, and increased perspective of employers into curriculum. While success may be measured by the value proposition to learners, the microcredential must also be validated by employers. One of the most challenging elements when planning and assessing microcredential approaches “is the personnel capacity and stakeholder capacity; the people on the ground really designing and implementing into the institutional structures” (Lisa Larson, 2022, personal communication).

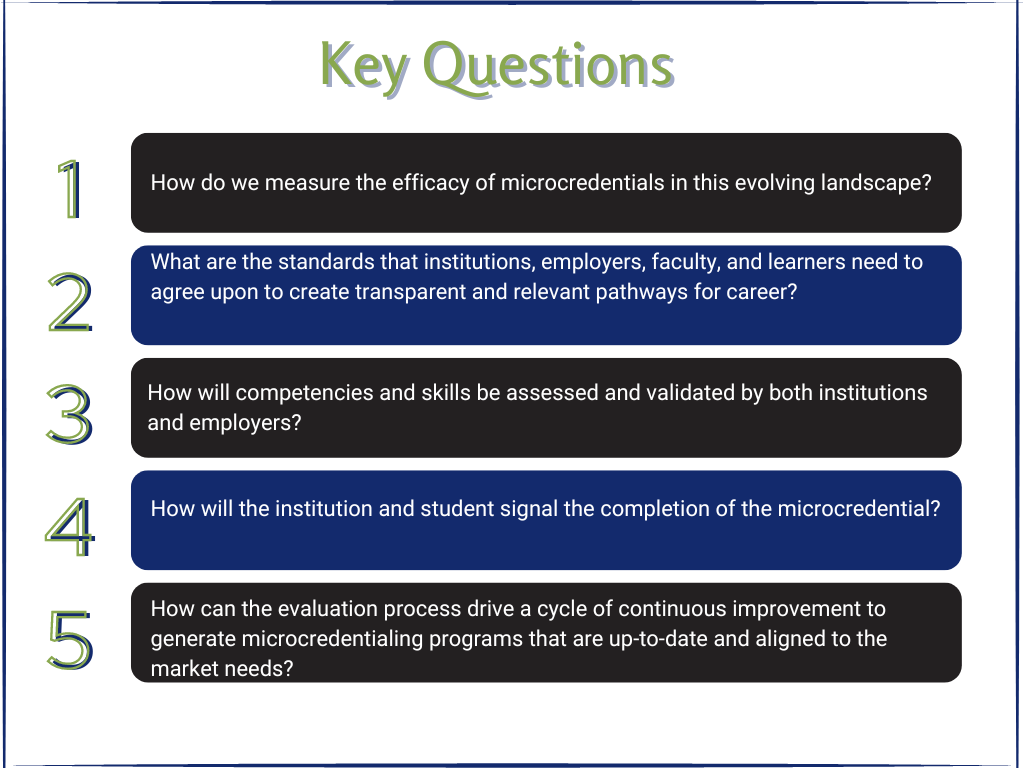

Leah Palmer, Executive Director at Maricopa Community Colleges Arizona Advanced Manufacturing Institute (AzAMI) emphasized the importance of data tracking and benchmark metrics to measure the impact on student success, costs to the institution, and sector demands for talents. Palmer recommends tracking the number of hits on your microcredential webpage, enrollments and trajectory, value propositions such as course completions, earned badges or certifications, and follow-up emails for employment-related status. We must create opportunities for enhancement and/or implementation of corrective actions during the microcredentials planning phase.

Micheal Voss, Dean of Instruction at Mesa Community College recommends an “annual threshold review of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and a more robust program review at least every 5 years. Ideally, program completers should receive follow-up surveys 12-18 months post-completion to gain feedback as to how the knowledge, skills, and behaviors learned have impacted the person’s employment or next step education status.”

Lori Lindenberg, District Director of Data Analytics and Strategy at Maricopa Community Colleges explained how their system of 10-independently accredited colleges shares data through the Student Clearinghouse Postsecondary Data Partnership (PDP) to assess the leading and lagging indicators typically associated with the guided pathways framework, such as credit momentum and time to completion. Measuring economic outcomes has proven a little harder for some institutions. Employment data is notoriously difficult to acquire yet increasingly important to track the impact of microcredentialing. Maricopa Community Colleges has a partnership with Equifax to study wage data (pre- and post-completion), annually for up to 10-years, but this has been traditionally focused on degrees and certificates. They are working to transcribe recognition of microcredentials into their student information system and also experiment with digital badging platforms. The country’s largest accreditor, the Higher Learning Commission, sees an opportunity to provide a quality assurance service for non-degree credentials, yet they note their current limitations in capacity and scope (HLC, 2022). Perhaps third-party validation will promote shared standards of quality and transferability of microcredentials.

Key Takeaways and Summary Points

Through the testimonies and insights gathered in this process, we have identified that different data points will be indicators of success based on stakeholder perspectives (Larson, personal communication, 2022). Institutions and employers should base their microcredential partnership on key values and standards such as transparency, validation, recognition, and reward of skills. Table 1 illustrates this point that the measures of success may be complex and individually defined. The value proposition of a microcredential often depends on one’s perspective.

Table 1. What success looks like by stakeholder group – words commonly used

| Student | Employer | Faculty | Administration | Accreditor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affordable | Meet a specific workplace need that directly support industry job roles and job descriptions that are in demand | Engagement | Meet a specific workforce development need | Quality assurance |

| Short-term | Recruit skilled workforce | Learning | Student’s success | Curricular alignment |

| Re-careering | Diversity equity and inclusion strategies for recruitment | Authentic assessment | Enrollment | Employability of graduates |

| Upskilling | Retain and reskill/upskill current employees | Retention | Retention | Transparency of tuition, fees, and costs |

| Recognition of skills | Career pathways | Completion | Complete | ROI for students |

| Career progression | On-ramps to educational pathways | Completion | ||

| Higher wages | Off-ramps to employment | Revenue | ||

| New job or different job | Stackable educational and career pathways | Digitally discoverable | ||

| Pathways to economic self-sufficiency | Curricular alignment to employment | Portable for the learner | ||

| Gain more confidence in career path and future | Career-ready | Valuable to the learner | ||

| Confidence to continue engaging in post-secondary education | Industry engagement and advisory | Validated by the employer | ||

| Effective demonstration of the target skills | Equity opportunities for students | |||

| Authentic alignment of the learning objectives and outcomes | Community engagement | |||

| Understanding of how to apply the skills | ||||

| Reflection on acquired competence and its corresponding outcomes–what the students should be able to do | ||||

| Concrete professional growth | ||||

| Relevance of the assessment and partnership with the industry/community |

It became quite evident that assessing and evaluating microcredentials will require rapid prototyping with inclusive feedback loops from students, faculty and employers. Microcredentials have shorter lifecycles and therefore continuous evaluation of KPIs and lead measures are critical. Table 2 shares examples of different KPIs for assessing and evaluating microcredentials that align to the ADDIE instructional design process.

Table 2. Key Performance Indicators to assess along the microcredential lifecycle

| Needs Analysis | Design & Development | Implementation | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional capacity | Stakeholder buy-in | Time-to-market | Student surveys |

| Personnel capacity | Employer engagement | Minimally viable product | |

| Feasibility analysis | Co-design between institutions and employers | Marketing leads | Student completion |

| SWOT analysis | Standards | Enrollments | Student intent fulfilled |

| Identification of skills gaps | Signaling completion | Alignment to industry jobs | Feedback about the positive outcomes of the microcredential |

| Technology needs | Transparency, validation, recognition and reward of skills | Employment opportunities | |

| Revenue generation | |||

| How and where the student shares the microcredential | |||

| Employer integrates into recruitment, hiring, retention, and promotion processes | |||

| Content quality | |||

| Improve the design of the credential |

Contributors

A heartfelt thank you to all the expert interviewees lending their time, leading this transformative movement in higher education, designing these critical learning experiences, and for helping us to measure what matters most. Interviewees included:

- Dr. Lisa Larson, President of Eastern Maine Community College, Ed Design Lab, Designer in Residence

- Lori Lindenberg, District Director of Data Analytics and Strategy – Maricopa Community Colleges

- Dr. Jude Chudi Okpala, Professor of Instruction- Department of Philosophy and Classics – The University of Texas at San Antonio

- Leah Palmer, Executive Director – Arizona Advanced Manufacturing Institute (AzAMI) – Maricopa Community Colleges

- Lydia Riley, Chief of Staff – The University of Texas System

- Scott Shireman, Global Head of Coursera for Campus

- Dr. Kate Smith, President – Rio Salado College- Maricopa Community Colleges

- Dr. Melissa Vito, Vice Provost of Academic Innovation – The University of Texas at San Antonio

- Michael Voss, Dean of Instruction – Mesa Community College – Maricopa Community Colleges

References:

Higher Learning Commission. (2022, April). Evolving: Accreditation and credential landscape. Retrieved on September 20, 2022 from https://download.hlcommission.org/initiatives/2022StakeholdersRoundtablePapers.pdf

Lazarewicz, K., Niles, G. (2022, May 26). Considering Your “Why”- How Developing a Microcredential Strategy Will Help Your Students (and Your University) Thrive. WCET Frontiers. https://wcet.wiche.edu/frontiers/2022/05/26/how-developing-a-microcredential-strategy-will-help-your-students-and-your-university-thrive/

Shireman, S. (2022, September 27). New Coursera survey shows high demand for industry microcredentials from students and employers in tight labor market. Coursera Blog. https://blog.coursera.org/from-higher-education-to-employment/